In the article following, world renowned hurdles Coach – Andreas Behm shares an excerpt from the ALTIS Track & Field Series Course – Coaching the Sprint Hurdles. Learn more here.

A couple of questions I often get asked by coaches are: ‘what hurdle spacings should I use during short hurdle training?‘ and ‘how do you determine what to use?’

I’ll start by saying that when we train main hurdle sessions we never hurdle on the actual race distance marks: We always discount the hurdles to somewhat shorter spacing for any type of full speed hurdle runs.

(We also often tend to hurdle with the hurdles a notch below race height; though there are instances and athletes who need to hurdle over the full race height to time things up into, over and off the hurdle).

The discount helps account for the lack of race excitement and adrenaline, and allows us to work on quick rhythmic units. It additionally helps the athlete perceptually get used to how quickly the hurdles will be coming “at them” during a race in which they are running really fast. The reduced spacing without adrenaline may actually give one the best race simulation conditions possible from a cadence perspective: If one tried to hurdle on the race marks in training this would lead to slower rhythms, more open postures and shapes, and increase the potential for reaching in the air, or over-pushing on the ground to cover the required distance. In short, it would actually provide a very different feeling from what the athlete would need to replicate in a race.

The main discussion point of this article is centered around thoughts about how much one could be discounting the hurdles. If you are reading this for a completely unified answer, well I have bad news – I have yet to come across one: In very general terms, however, we start out early in the year with hurdle spacings closer together, as the athlete is not as fast and powerful as they will be at a later time of the year. Then, once the athlete has stabilized speed and rhythm at a certain spacing, we move the hurdles out a little bit.

(I have progressively increased hurdle spacing by 6 inches, or as subtly as 1inch for the hurdle unit (depending on the progress and situation). There is undoubtedly also some intuition and artistry involved in finding proper hurdle spacings as it is not just a strict, rigid progression.)

Ideal Hurdle Spacing

Does the ideal hurdle spacing exist?

Probably not: Each hurdler will tend to have a preferred hurdle spacing as they get into the main part of the training season, and it is to the coach and athlete to determine what this ideal spacing is. This spacing is the one used during the main hurdle training session of the week where are implementing longer hurdle flights, with full approach, and trying to run these reps as quickly as possible.

There of course can be other sessions where a different spacing can be used depending on the session objectives and technical demands that come into play.

Be aware however, that this main spacing can change depending on a myriad of factors such as athlete speed, technical proficiency, the skill one is trying to emphasize, improved aggression, or strong winds etc… It is a fairly agile, adaptive and fluid process, that certainly involves some trial and error to figure out.

I have had the good fortune of working with a variety of different hurdlers, and various hurdle spacing preferences. Aries Merritt prefers his hurdles in fairly tight; he likes the feeling of turning over and shuffling really quickly between the barriers. His hurdle reps look fast and fluid with a -45cm unit discount. (That is roughly a 4.9% discount from the original unit distance).

Chinese hurdler Xie WenJun, on the other hand, prefers a very small discount. He likes to have the hurdles further apart, so he can power through his runs and doesn’t feel too jammed. His favorite spacing is only a -14cm discount (so only a 1.5% discount compared to race spacing).

On the female side, Queen Harrison also preferred a more open unit spacing – somewhere around only a -20cm unit discount (a 2.4% discount from race distance).

In a more extreme case, we had Canadian hurdler Astrid Nyame use a -65cm discount (7.6% discount) per hurdle. She is a tall and rangy athlete, and consistently has trouble with running up on hurdles. So we forced her to really take small steps and control her range of motion by jamming in the hurdles super close: Mind you, this did not happen all at once. We were a little more conservative with the discount initially to see what she could handle – and as she kept rising to the challenge we kept increasing the discount as we went along, until we arrived at a 7.85m spacing. This carried over well into competitions, and helped her pattern how to move in between and stay away from hurdles through the middle of her races.

It is oftentimes the case that I will have multiple lanes of hurdles set up for different athletes at various unit spacings. This allows for each athlete to have their preferred spacing and best flow through the hurdles.

World Record Velocities

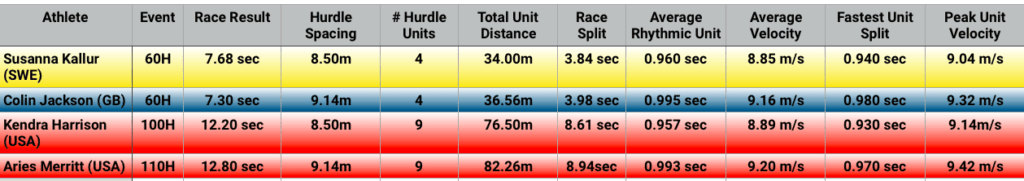

To take a deeper look at spacings we need to consider the velocities and rhythmic units athletes are able to generate. As such, I did a few general calculations with the splits from the current World Record Holders as an example.

Classically, hurdle splits have been timed from lead-leg touchdown to subsequent lead-leg touchdown off each hurdle – these are oftentimes referred to as ‘rhythmic unit times’.

In the chart below one can see the average and peak hurdle unit velocities that both the male and female World Record holders hit respectively. This can help inform training design based on the current human limits in the event.

As one can see even the most elite hurdlers “only” hit peak speeds of no more than 9.5m/s in a race. This is well below their sprinter counterparts velocities on the open track. Make no mistake about it though, considering these guys have 5 to 10 obstacles in their way, they are ROLLING!!!

Note I – these average velocities are taken on the fly, as the athlete was already in motion from the approach through the first hurdle.

Note II – I realize this is not 100% accurate. Athletes don’t always have the same exact takeoff and touchdown distances for each hurdle. Each unit consists of individual times on the ground versus in the air. But for this thought exercise let’s not get lost in minutiae, and keep our focus on the big picture message.

Rhythm vs. Velocity

Figuring out the proper hurdle spacings for an athlete can be a very subtle process, and one in which we should ask the following questions:

What is one after: Quicker rhythms or higher velocities?

Can we get both? (Hopefully!) It all depends on what the athlete can handle and what they are suited to best.

Which technical components is the coach trying to work on?

As mentioned before, training spacings will almost certainly need to change as an athlete gets faster and more powerful throughout a season.

Realize also, there can be a trade off between quick rhythmic units and velocities: The tighter the hurdle spacing, the quicker the unit time – yet the ground covered – and hence velocity will not be super high.

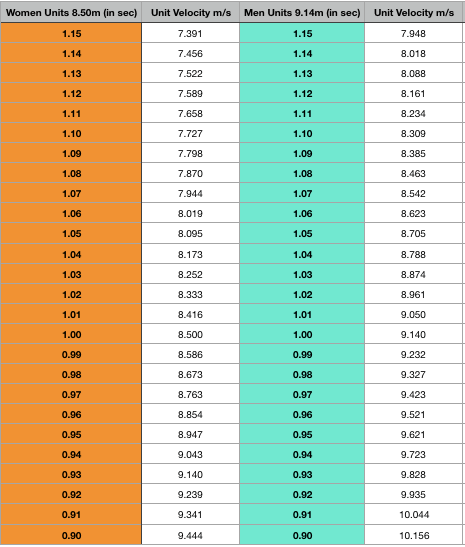

Below is a chart to show velocity for a full race-space hurdle unit, based on the corresponding rhythmic unit split achieved. This gives coaches an idea of how fast an athlete was going for an individual unit within a race:

Ultimately, the highest velocity through hurdle units wins the race. The key is to find the best spacing for a given athlete that transfers their rhythmic capabilities in training to actual race velocity when the gun goes off!

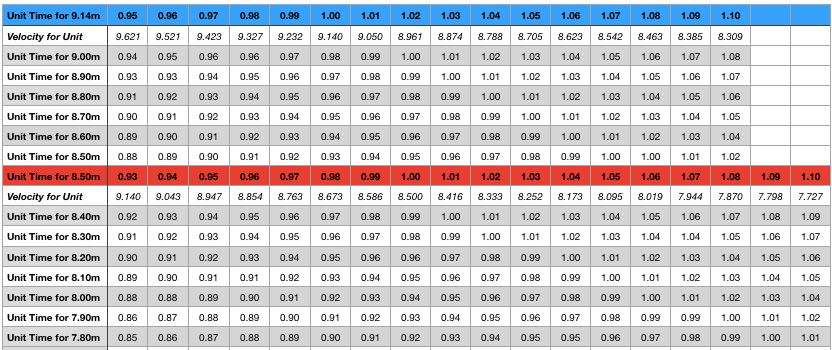

So, should you accept slightly slower splits at slightly larger hurdle spacings?

As one can see from the examples below sometimes a slower split with larger hurdle spacing yields a higher velocity. In many cases the answer is pretty straight forward, but as one gets closer and closer to the same hurdle spacing, a 5-10cm swing can make a difference for an athlete – and as we all know – races can be won and lost due to the fraction of a second.

Example 1

1.02 sec unit split at 8.30m resulting in 8.14m/s

1.01 sec unit split at 8.20m resulting in 8.12m/s

Example 2

1.02 sec unit split at 9.00m resulting in 8.82m/s

1.01 sec unit split at 8.85m resulting in 8.76m/s

In both examples above we can see that the slightly slower timed split with a slightly larger hurdle spacing yields a faster velocity. So just basing progress and hurdle capability on splits alone may not always be sufficient. Having the context of the spacing involved adds another layer of crucial information.

The chart below shows equivalent velocity and hurdle split times for standard distances that are commonly used in training. This allows coaches to compare and contrast splits at various spacings, and see how they stack up against each other.

It also allows coaches to look at this in the reverse. Decide the velocities you would like to hit in training, know what splits a given athlete normally runs, and then set the hurdle distance accordingly. One can work this either way.

(* with the general understanding that the improvement in unit time would need to come from the time spent on the ground, as flight time would remain relatively consistent).

Flow & Technique

We have talked a lot about comparing splits and velocities, but we have so far left out one very important training question: Does it flow?

If only hurdling were as simple as just following the numbers!

A big component of hurdle spacing is the movement quality and fluidity displayed by the athlete executing the reps. This may go hand in hand with faster times – but the importance of this cannot be overstated:

- Can the athlete do a certain spacing? – yes! Is it decently fast? – yes!

- Are they straining to do this? – yes! -> then maybe this is not a great idea (yet): It may only be a matter of time before an athlete breaks down.

Find a spacing in training that allows the athlete to execute movements fluidly, and one can work on layering more speed and power on top of this. The eventual reward will then be to move out the hurdle spacings at a later point when the athlete is more prepared to handle that distance. This is where the experience, artistry, and discretion of the coach comes in – big time!

There are obviously also technical considerations for choosing a certain hurdle spacing: Not everything needs to be full-speed, all the time.

As such, you should consider asking yourself…

- Does spacing negatively impact technique of steps in between?

- Is the ideal takeoff distance and/or takeoff technique compromised?

- Is the athlete so crowded that they become too rigid in their movements?

- Is the athlete too stretched so that they are over-pushing on the ground, excessively straining, or reaching?

- Can an athlete produce the same movement outcomes with different spacings? Are they stable no-matter the variability of the constraint?

More to Explore

There are many more topics to be covered and explored on this subject, including:

- hurdle spacing progressions

- spacings for 1-step and 5-step

- zones

- contrasting different hurdle spacings or even different unit spacings within a rep

- manipulating hurdle heights to achieve faster splits.

These topics will be covered in-depth within the ALTIS digital hurdle course.

Shout-outs to Coaches PJ Vazel (France), Jan May (Germany), and Todd Henson (Team China) for providing the split data and advice. Thanks also to Dr. Ken Clark, Malcom Hairston and Kebba Tolbert for reviewing and providing feedback on this article.

Hopefully this small excerpt encourages you to evaluate your own training methods with regards to hurdle spacing selection. Combining science with art, and considering the individual needs of athletes you work with will go a long way in continuing to help further your training philosophy.

Thanks for reading!

Andreas