Derek Evely is one of the world’s foremost experts on the theory and methodology of training, with a special interest in the work of Dr. Anatoliy Bondarchuk (Derek was the person responsible for bringing Dr. B to North America, and Dr. B lived in Derek’s basement for 5 years!)

Derek – along with our great friend, journalist, coach, and super-historian of all things track and field, PJ Vazel – wrote significant portions of 3 modules within the Foundation Course, including much of Module 5.

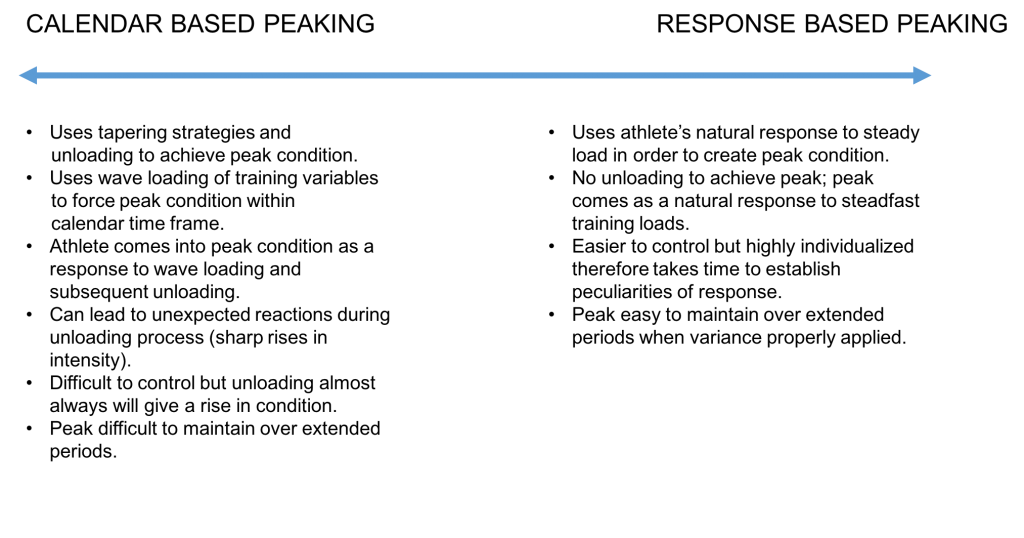

The following short section is from Module 5; Section 5 (Module 5 is entitled Planning & Organization), and Derek outlines the difference between ‘calendar-based’ peaking and ‘response-based’ peaking (which is the Bondarchuk methodology) . We also include a short video of Derek talking about peaking and tapering, as well as some written tips on tapering.

We hope you enjoy!

REACTION / RESPONSE BASED PROGRAMMING

In its strictest sense response, or reaction-based programming does not use the manipulation and variation of training variables in order to force adaptation the way traditional periodization does. Rather, it uses no (or minimal) wave loading of training variables and abilities, plus strategic changes in qualitative elements of training, in order to plan training. These changes are based upon an athlete’s response to a steady state training stimulus.

In simple terms, this means rather than predicting that an athlete will peak, say, at the end of a 3 month cycle that is made up of various smaller cycles (each of which utilizes a set of distinct loading parameters) a coach instead will track how long it takes an athlete to come into peak condition, using a consistent set of training sessions, and measure an athlete’s response to these sessions via specific, or near-specific measurables. This response determines how long an athlete needs to prepare to come into peak condition.

Time to reach peak condition is actually based less on time, than it is number of exposures to the sessions presented to the athlete. Once this number is found to be repeatable and reliable, future cycles in the medium term plan are built upon this strategy. This is based upon the work of Dr. Anatoliy Bondarchuk, but also can be applied to those who prefer to plan in the medium term – albeit employing intra-cycle variation – rather than using longer-term annual plans for peaking.

In either case, the use of a clear and consist set of specific training measurables is critical in order to measure an athlete’s response – or adaptation – to training.

The following criteria will help in your understanding of this method:

- Rather than pre-establishing the attainment of competitive form based upon calendar timelines (periodization), in this type of programming an athlete’s time to reach a peak “condition” is measured using a minimum of wave-loading organization.

- This type of planning does not rely on the traditional Annual Plan, but rather “macro” type planning formats (phases or intervals of time that are the equivalent of a modest collection of microcycles).

- In order to be effective when implementing this type of planning strategy, one must have highly specific measurables: The more specific the measurable, the more accurate the planning will be.

- Once identifiable reactions to specific measurable training inputs are established, the process can largely be repeated.

- The less wave loading of volume and intensity, and the less random or chaotic changes within the delivery of the training program, and the more reliable an athletes response to training is. Change within the cycle itself leads to two effects upon the “time” to peak condition:

- 1) it is less reliable (harder to repeat)

- 2) it delays the peak (peak takes longer).

With reaction / response-based programming the density of training is your key planning variable, or tool. Early and mid-season reactions to training will then give you the data you need to plan late-season peaking plans.

CALENDAR BASED PEAKING VERSUS RESPONSE BASED PEAKING: A SUMMARY

The graphic below is a handy reference summarizing the key differences between these two methods.

PEAKING AND THE NEED TO TAPER

An important element in any discussion around planning and organization is the concept of peaking, or ‘sport form attainment’. In simplest terms peaking is a rise and subsequent crowning of an athlete’s performance in the competitive event.

This may occur at the level of the medium-term cycle, annual cycle, or even multi-year cycle. However, from the perspective of planning the various abilities and elements that ultimately compose an athlete’s performance, we must consider just because an athlete achieves a cycle best, season’s best, or even lifetime best performance, is that truly a ‘peak’ performance?

In the case of the latter it surely is, of course. However, relative to one’s past performances or future potential this simple definition may not be at best enough, or at worst, misleading when we are reviewing our own programming, and trying to determine if our past programming has been effective.

In other words, just because our athlete had their best results in the competitive event at the end of a given cycle – was that truly a peak? Perhaps it was- but could it have been better?

Bondarchuk’s definition is perhaps the most comprehensive and appropriate when defining a peak in the context of programming and cycle design:

“The term ‘Sport Form’ refers to the best condition of physical, technical, psychological and tactical preparedness of the athlete. This condition occurs at the end of the Period of Development of Sport Form (PDSF). If the PDSF is composed of stages or blocks, peak condition will be realized at the end of the stage or block. The term “Sport Form” was initially used over 40 years ago in Soviet sport theory and practice. In other countries this condition is referred to as ‘top form’, ‘best shape’, ‘best performance’ or ‘peak condition.’”

– Bondarchuk, unpublished writing, 2005

*Note: The PDSF is synonymous with what we describe as the “Development Cycle”. It is composed of a collection of microcycles at the end of which an athlete attains peak condition.

PEAK CONDITION?

We must ask the following questions to accurately ascertain if we are truly seeing a peak performance:

- How many performances constitute a peak condition? One? Two? A week’s worth?

- What is the pattern of results that lead to that peak?

- If an athlete is in heavy training for an extended period, and then we suddenly unload that athlete and he/she achieves a rise in performance – is that a peak?

- Also, how superior a performance relative to others in a cycle does one need to see to determine if a peak has occured?

These are important questions one needs to ask when determining what a “peak” means, because it speaks directly to the peculiarities of an athlete’s response to training.

VIDEO STOP:

Further thoughts and discussion on tapering and peaking.

TO TAPER OR NOT TO TAPER?

One of the most ubiquitous and common practices in all of training and coaching tradition is the tapering cycle. That is, a gradual unloading and reducing of workloads during the final phases of training into a competition or training cycle. The purpose of such cycles is to reduce or remove residual fatigue effects and allow an athlete to enter sport form. It most certainly works, especially in programs where there is heavy loading of volume and intensity. However, tapers can be difficult to time and manage.

In final phase preparation for major championships they may work well, however, for early season competition, or in periods where the resulting sport form must be maintained for extended periods, they can be notoriously ineffective.

Some training theorists and coaches believe that a tapering approach does not represent the achievement of a true “sport form”. It is simply “unloading an athlete” to achieve a rise in performance. They argue that this is merely pushing a spring down all year and then simply releasing the spring prior to competition.

Many coaches have learned the hard way that some athletes do not respond well to acute unloading, and instead need a regular, constant load through final phases in a cycle to achieve a peak condition. These athletes may respond to a taper, but those tapers must be very short, because with too much time away from loading they will negatively respond. Add to this the differences in competition demands (speed / power vs. endurance, team vs. individual) and one has a lot to consider when designing program and peaking cycles.

Consider this: how many times has one witnessed in training superior, even career surpassing performances in moderate or even heavy training cycles? A common response to such an occurrence is to simply think “wow, once we taper performance is going to go through the roof!”… and then it doesn’t, and in many cases, it gets worse with acute reductions in load. This, unfortunately, is a common occurrence in holding camp situations where athletes are initially training at high load, responding well, and then unload into a championships situation – only to be disappointed by the final performance.

PHILOSOPHICAL DIFFERENCES IN LOAD MANAGEMENT

Tapering vs. non-tapering approaches are more complex than what is simply happening in the final weeks before competition. They represent philosophically different approaches to developing athletes and the management of loads. One approach prefers to load and then unload within a calendar structure to achieve sport form. The other prefers to maintain a constant loading, while managing variation within the cycles to achieve an individual and predictable adaptation response: This approach is therefore, theoretically, a more reliable and consistent peaking process.

Sometimes we observe these approaches being implemented before us, and do not even notice it. For example, often in championship settings we observe other performers’ training in shared camp situations, and notice relatively high training loads leading closely into the competition date. Coaches can be bewildered by this, and oftentimes will attribute other reasons for such a phenomenon – other than it is simply that they are using a non-tapered approach. Many a young coach has been misled by such observations.

The need to taper is directly related to the qualitative and quantitative nature of the program design. High load cycles with controlled variance will bring athletes into sport form without tapering, but this pattern of response or reaction must be experimented with away from the competition period. Cycles that do not wave load volume and intensity will find that the athletes performing such work will come into a natural peak. This peak is considered by some to be a “true” peak: one that is higher, more sustainable, and longer lasting.

Remember, tapering is variance and a change in loading … and change is sometimes difficult to control (chaotic change is impossible to control). Change is a powerful tool in a coach’s arsenal but needs to be respected and coordinated. It can be your best friend and your worst enemy.

For example, changes within a training cycle will result in an extending of the time to peak condition. This can be very helpful if you find your athlete in peak condition weeks out from a major championship, and you do not have enough time to enter another development cycle. A long, formal taper here would not be advised, but rather a continuance of the loading scheme, with regular and planned changes in content to sustain an athlete into the competition dates.

TAPERING TIPS

So what approach should one use? One needs to experiment to find out, but here are some tips:

- Don’t experiment with tapering cycles during the final phase of a competitive season. If you are going to use a taper, use it in prior training cycles to get an idea of whether it is going to work or not.

- Make sure the taper is of the appropriate length. Athletes who need work will need short tapers. In contrast, athletes who are very sensitive to work may need a longer taper, because sudden reductions in volume can bring about abrupt increases in intensity that they may not be accustomed to, and therefore may lead to injury. Tissues and musculoskeletal structures need time to adapt to changes in intensity. This is Rule #1 in keeping athletes healthy.

- If you are going to use a non-wave loading approach and forfeit a taper, then make sure, as with using a taper, that you have used this approach in training and can repeat and re-create the athlete response.

- PAY ATTENTION to athlete responses in training. Make notes. Track things. Unexpected rises (or reductions) in training performances are telling you something. Look to your training data to see where the best performances are … examine what types of loading led to the peaks in both a qualitative and quantitative sense.

- Further to the above: When evaluating performances in training, and trying to establish a link or transfer to training content (cause and effect), evaluate not just the cycle, but the results from previous cycles as well. Over time, see if you can establish the occurrence of delayed training effects. Sometimes an athlete’s response to the current program occurs in relation to the content of a previous cycle. Such relationships can be difficult to establish – but are worth exploring.

- When prescribing final phase loads, always err on the side of caution. However, be careful with a fear of pre-competition overloading. Many have lost championships because of too much unloading … determining this is the art of coaching, backed by science and empirical evidence.

I am a Strength & Conditioning Coach. Is the Foundation Course for me?

The role of the S&C Coach is becoming less and less about Loading bars, and counting reps, and more and more about becoming a generalist practitioner – who understands sport performance from a multitude of different lens – including the importance of how to develop, program, and progress speed abilities.

Besides there being significant information on programming, training methodology, and progressions related specifically to strength & conditioning itself, everything else that is in the Course is relevant to an S&C Coach – kinesiology, biomechanics, training methodology, speed development, etc.

I’m a high school cross country coach and also coach middle distance track athletes. Would this course be applicable to my needs and serve my distance runners, or is this mainly geared toward sprint coaches?

The concepts shared in the Foundation Course are written in such a way as to be applicable to all coaches in sport. It is not until the final couple of modules where we touch upon speed and strength – but we feel this is increasingly applicable to distance athletes – where speed is still the limiting factor!

Starting with a fairly in-depth exploration of the fundamentals of physiology, biomechanics, kinesiology, and then moving on towards training methodology, programming, and training progressions, and finally to more speed and power concepts, we really feel it can be very valuable for all who work in sport – including distance coaches.