Chidi Enyia is a sprints Coach at Altis. He made the move to Phoenix in September 2014 following a successful term at Southern Illinois University, where he served as a Sprints Coach for four seasons. In this article, Coach Enyia introduces how acceleration is taught at Altis – beginning with block setup.

“While exploring the important qualities necessary for success in all sprints, it’s very reasonable and responsible to place a great deal of emphasis on maximum velocity. That being said, without effective and efficient acceleration mechanics, maximum velocity potential is greatly compromised.

I’m not a violent man by any means but I do encourage massive amounts of unwavering

violence in this particular environment because it is necessary for its optimal execution. It is important to understand that to optimize maximal velocity, acceleration cannot be timid; maximum commitment to each step, and an understanding of efficient mechanics of acceleration is the key to maximizing maximal speed.

Please note that we do not separate the race into distinct ‘phases’ (i.e. drive phase, transition, and top-speed); instead, it is important that the athlete sees the race as one complete, seamless acceleration. While breaking the race up into sections may serve some purpose for coach analysis, it is better that athletes regard the race as one continuous, holistic run. Also – this is the general model; and while this forms the basis of what we teach towards, every athlete will have their own individual variation of, and solution to it.

Block Set-up

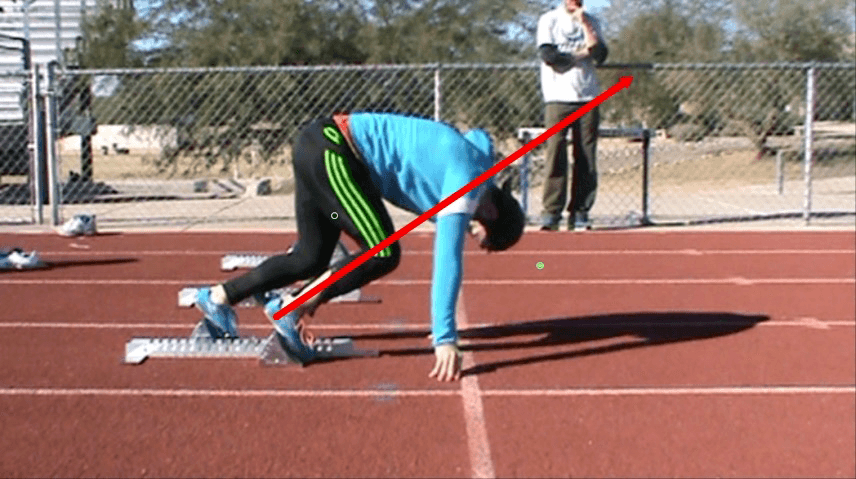

An ideal, mechanically advantageous position for maximal force delivery into the blocks must be employed for great starting power and efficiency. What this means is the initial block set-up must be extremely accurate – and will not vary greatly between athletes. As seen in Figure 1, the shoulders are positioned directly over the hands, while the front knee brushes the elbow and the rear thigh is perpendicular to the ground. Also, the head is in line with the spine and the back is flat. Once the athlete rises, the front foot will be positioned slightly behind the hip for immediate force production upon projection. If the front foot is set in front of the hip line, the block exit will be less optimal because of the time it takes to reposition the hip in front of the foot for thrust. Hands should be shoulder-width, and actively pushing into the ground, almost rounding the upper spine. The further the chest is from the track, the more efficient will be the unfold into extension upon initial projection.

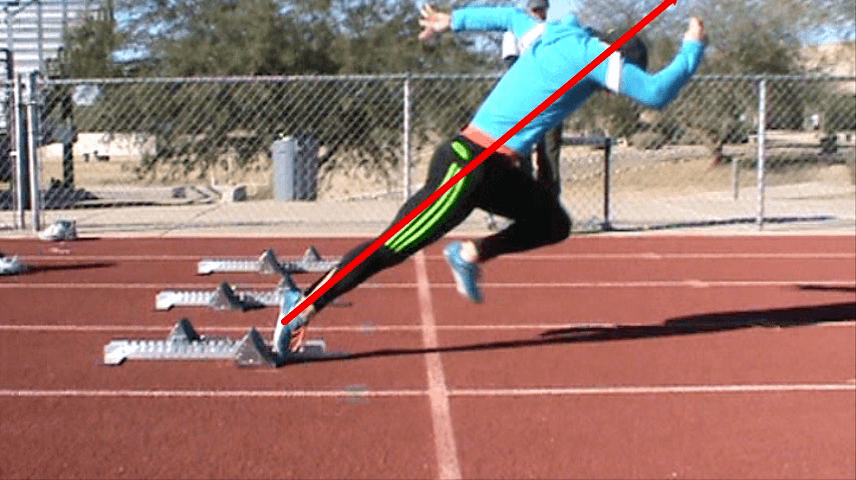

In Figure 2 below, the athlete has risen to the set position with the hips slightly higher than the back and the head relaxed and in line with the spine. Shoulders remain directly over the hands and the front and rear legs are opened to ~90 and ~120° respectively. Notice how the front foot is still slightly behind the hip line for rapid, timely force application. Also, both feet are pressed completely against the pedals with the ankle joints locked into place for efficient energy transfer once movement is initiated.

With the shoulders over the hands and the legs at the appropriate angles, weight is evenly distributed on the ground creating stabilized and controlled posture for the athlete to push from.

Block Clearance

In this set position, preparation to deliver a large reaction force into the pedals is optimal.

Force will be returned equally and in the opposite direction in the form of a straight line through the shin from the malleoli, and through the middle of the shoulder joint, at an angle between 40 and 45 degrees relative to the ground. This angle will be determined based upon the relative force generating characteristics of the athlete, as well as specific morphological considerations, among other things. Generally speaking, the stronger and shorter the athlete, the lower this angle can be. It is important that the athlete pushes back hard though the heels onto the pedals, as this will set up appropriate levels of pre-tension so as to minimize vertical drop of the front knee and shin upon initial projection.

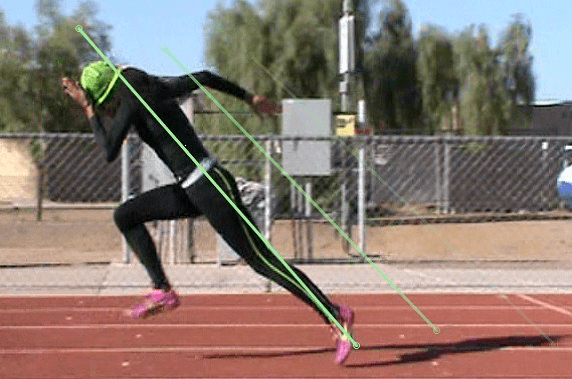

It is critically important that the athlete push into a ‘high-post’ – VIOLENTLY and COMPLETELY up, with a large sweeping action of the arms as the shoulders travel along the line of force. At its completion one should observe the ankle, knee and hip within that same line so the entire force can travel through the body to maximize the velocity and distance of the launch (Figure 4). If they do not push up along that line, the hips will stay behind and they will be bent over at the waist (Figure 5). This type of faulty posture leads to a loss in energy which ultimately means decreased velocity.

To avoid these issues it’s important to stress patience and power through a full range of motion, as opposed to quickness. Do not stress quickness at the expense of range of motion, because that mentality tends to produce rushed acceleration patterns that lead to energy distribution issues in the sprints. Long, deep pushes and longer ground contacts must be emphasized consistently.

Acceleration Progression

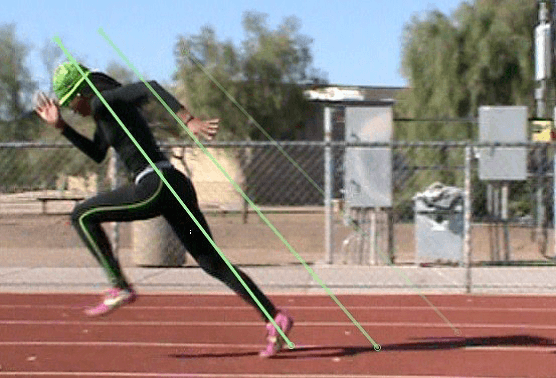

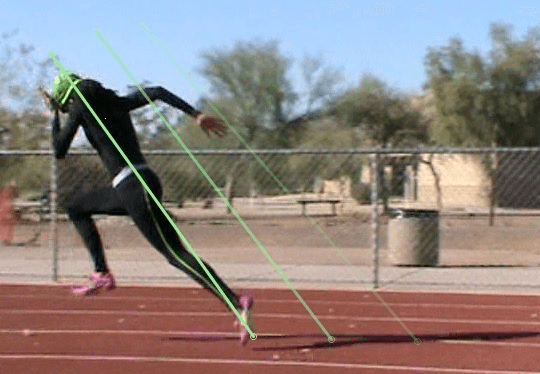

When the athlete has posted up from the blocks and continues to progress, you should be able to draw an imaginary straight line from the ankle through the ears, and the front shin of the swing leg should be parallel to the angle of the body. From this position, they should actively push the feet backwards to the track so the ground contact happens at or slightly behind the hip (Figure 6). This is necessary for immediate acceleration since braking force is minimized and the body does not have to spend valuable time repositioning itself back in front of the foot for propulsion (ground contact in relation to the center of mass will move from a point behind to underneath, to in front, in a gradual manner – and though we want a ground contact behind the COM for the initial steps, it is important that this point is not too far behind, as this will lead to an overly horizontal projection, a loss of balance, and either a lateral projection, or an excessive lower-leg swing).

Problems occur when the shin of the swing leg is cast out – causing it to land in front of the hip where the athlete has to pull themselves forward with the hamstrings. Ground contact too far in front of the COM will also compromise ankle rigidity, ground contact time, and subsequent energy loss through the system. Excessive lower-leg swing can be due to pushing back for too long, and not rising with every step; structural abnormalities through the pelvis, sacrum, hip, and/or knee joints; or incorrect understanding of the movement pattern. The Athlete is to be instructed to rise the hips and shoulders with every single step. No step should look like the step that preceded it – as velocity – and therefore, kinematics – change with every step of the run.

As the athlete is accelerating up the track, multiple smooth transitions are taking place:

Thighs and heels will go from piston-like to cyclical action (as a result of increasing velocities, joint stiffness, and muscular co-contractions – not changing cues);

Ground contact time decreases;

Flight time increases;

Heel recovery height increases;

The body rises with every step until maximum velocity is reached (Figures 7a-e).

In addition, it is important to cue the continual and/or increasing aggression of each step and a smooth transition to upright, as opposed to staying unnaturally low for a forced amount of time.

Conclusion

Acceleration development forms the basis of Altis technical model, and is an essential part of training every single day – from the first day of the season. Every session, athletes will run a minimum of 3-5 accelerations, and it is imperative that the athletes embrace and express the general spirit – i.e. violent, maximal pushing with rhythmical and patient rising of the hips and shoulders with each and every step until fully upright. It’s important to focus on the fundamentals, revisit them often and be patient enough to execute necessary volumes of repetitions, with intention and purpose for mastery.”

Chidi Enyia is on Twitter – you can follow him here.