Each of us comes from chaotic environments with different constraints, challenges, and bottlenecks. Even though we all share a similar goal – performance – it is challenging to directly help solve each other’s specific problems.

The complex worlds we live in consist of unique interactions between the elements that make up these worlds. Our context is different. Therefore, the most we can hope for is to provide an improved vantage point to approach these problems from. This is where Problem-Driven Solutions come in.

Before we can discuss what this vantage point may look like we need to ensure we are on the same page. We must all share a respect for the complex environment we operate in and humility in our inability to accurately predict. These are facts. These facts mean we must allow the ‘output’ to guide our decision making, interventions, inputs, programming, sports science initiatives, etc. and it all starts with learning.

Problem-Based Learning

Traditional Learning involves memorization and implementation. It is your classic ‘Concentration’ card game where you memorize the location of face-down cards and match pairs over time.

In contrast, Problem-Based Learning tells us to identify the problem, identify what we need to know to solve the problem, acquire this knowledge/wisdom/experience and apply. It is the classic puzzle. You zoom out to look at the big picture (output). You divide this big problem into manageable chunks. You zoom in to identify the pieces. Along the way, the output – or those pieces that are put in place – drive our future actions. Through trial and error we can determine the final resting place for each piece.

Traditional learning creates cooks – problem-based learning creates chefs. It pushes us towards the probe-sense-respond framework from Snowden to manage complex problems.

Using the Output in Sport Performance

An excellent example of programming based on the output comes from Dr. Anatoly Bondarchuk. His system of training elite throwers was rooted in the consistent collection of performance outputs. Over time, these outputs would lead to trends and patterns that, when correctly identified, could offer direction for the programming leading up to major competitions. Bondarchuk reduces the ‘noise’ by not wave-loading volume or intensity. Rather, a change in exercise selection is the driver for adaptation- but only after the output has presented signs of a performance plateau.

Due to our inability to accurately predict, we must allow the output to guide our decision making. Our micro-cycles must dictate our meso-cycles and our sports medicine interventions must build off of one another.

With all the uncertainty present, we need a framework to help us navigate this landscape. Fortunately, a man named John Boyd has provided us with such a thing.

The OODA Loop

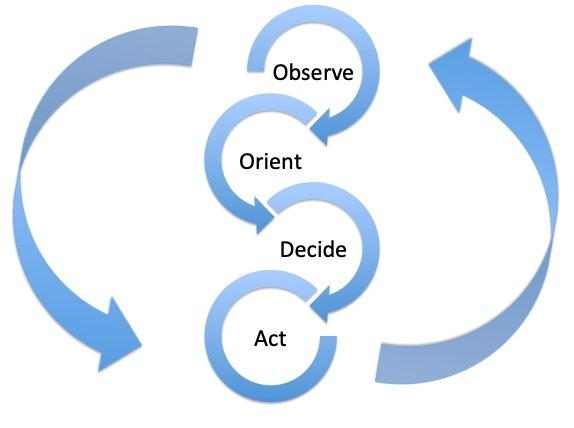

John Boyd was a fighter pilot in the Korean War and is regarded as one of the greatest military strategists of all time. Through a series of briefings, Boyd identified a 4-step method that helps us deal with uncertainty – observe, orient, decide, and act.

From a wartime standpoint, whichever side was able to progress through multiple OODA Loops most effectively and efficiently would have the upper-hand.

In these scenarios, time is of the essence. Therefore, tempo becomes critical. As you can see, feedback loops are abound and the tightening of these loops allows for a greater number of iterations, a greater number of experiments.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, we must first observe. Where orientation used to be thought of as the most challenging of the 4 steps, we would argue that observation poses the greatest challenge in the world we live in today.

Just as in a sprint where every step is a product of the step that preceded it – the initial stage of the OODLA Loop is arguably the most important…and challenging!

The Role of Observation

The vast amounts of stimuli working for our attention is like nothing humankind has ever experienced before. With ridiculous amounts of financial support and intelligence working towards capturing our attention through technology and other means, as well as the hectic nature of the ‘rat-race’, our ability to observe is extremely compromised.

What can we do to offset these challenges?

The first step is occupying a state of Condition Yellow. Again from a military background, Condition Yellow is a state of readiness and alertness despite no immediate threat. It means we are fully aware of our surroundings. Watching everything. Aware of our positioning within the environment. Setting ourselves up for the collection of information and initiation of the OODA Loop.

Now that we are in a position to observe, we must bring in the idea of models. The development of mental models specific to the environments we work in can serve as anchors.

As we are all aware, an anchor prevents a boat from disappearing while still allowing some movement. In each instance that we drop anchor, we must determine the appropriate bandwidth or deviation from that point that is acceptable. This movement around the anchor point can be thought of as the bandwidth in movement expression we will see around a fixated technical model.

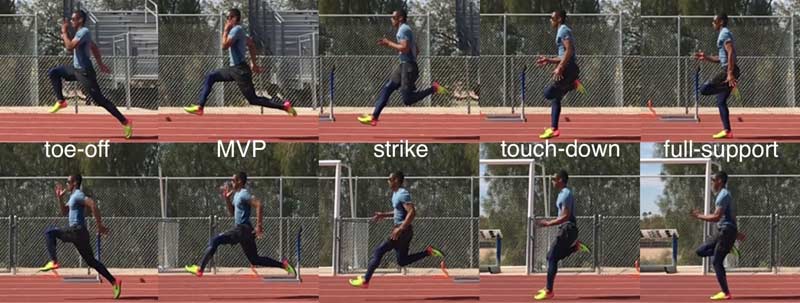

In sprinting for example, there is in fact a technical model. There are key positions or attractor states present. But there are also individual bandwidths within.

Which is why, although mental models are crucial, we must use them cautiously. Models are often built from averages and can ignore individuality.

In his book, The End of Average, Todd Rose discusses 3 key principles that we must remember in order to not lose sight of the potential pitfalls of models.

The Context Principle – Behavior is not determined by our traits or the situation, but an interaction of the two.

The Jaggedness Principle – Our talent cannot be reduced to a single metric, such as a standardized test score.

The Pathways Principle – Arguably the most important of the 3 in this case, the Pathways Principle tells us that two individuals may be at the same stage and progressing towards the same end goal – but that doesn’t mean they will take the same path. Or that there is one best path for both!

Most often it is not linear – we are not simply climbing a ladder. Rather, we are navigating a maze. And within this maze we will undoubtedly take wrong turns. It will be an iterative process of trial and error.

We must adjust based on the output and we must allow for the expression of individuality.

Therefore, after identifying key technical landmarks that apply across large populations, we should be looking at individual movement solutions over time in relation to this. As a well-rounded Sport Performance team we must all develop our observational abilities.

The Coach’s Eye and Decision Making

The first stop along the developmental path of our ‘coach’s eye’ is still images. Just as an athlete needs to be exposed to progressive overload, we need to start simple and build our capacity to accurately observe movement in real time.

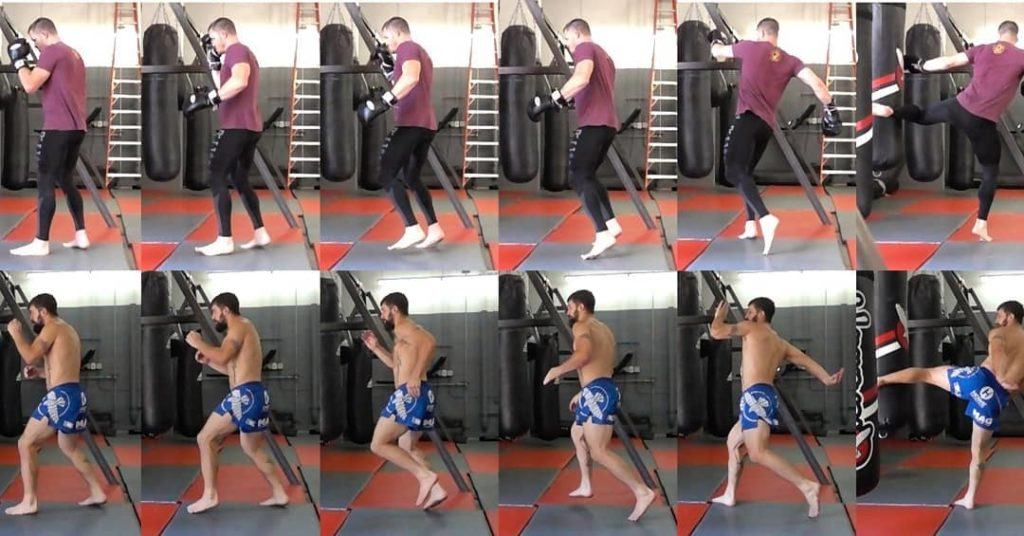

The ALTIS Kinogram Method can be an extremely useful tool in this regard. Here is an example of an upright sprinting kinogram showing each limb through 5 key positions and a kinogram taken from the world of MMA.

As we progress our observational abilities from still images to real-time we open up the opportunity to make decisions when and where they matter most – within the Performance Environment.

As previously mentioned, the tempo that we progress through the OODA Loop in is crucial. In most situations, the decision needs to happen immediately, with the best case scenario being a swift transition from orientation into action. The decision happens in the blink of an eye based on keen observation and orientation. It is often times simply a hypothesis or best-guess.

But what is it that we are looking for out of this hypothesis?

Within the decide stage we are ultimately looking to have an immediate impact through intentional action, or inaction. Many of us in the Sport Performance world would likely fall under the category of ‘control freaks’ – we like to get involved and intervene. We like to be in control, which too often means taking action. Before we do so though we must ensure their is intention behind our action and we are not intervening for the sake of it.

“The human body is a complex, natural thing. It was shaped by millions of years of trial and error, mutation, adaptation, and genetic selection. Like a society or an economy, it is more likely to be damaged by heavy-handed intervention than improved by it.”

Hormegeddon

With this, it is important that each of us as individuals within the Performance Team accepts accountability. More specifically, outcome accountability over process accountability.

Process vs Outcome

Process accountability can be thought of in terms of Standard Operating Procedures. When following step-by-step processes it is easy to navigate through mindlessly. We are line cooks as opposed to chefs. We lose any concern for the output because we’ve “done our job”. We become ‘Yes Men’ and ‘Yes Woman’ who clock in and clock out – losing all ability to think critically.

Standard Operating Procedures may have a time and a place but proceed with caution.

The structure should be loose, allowing for artistic flow to still take place. The discipline to understand the structure, to observe actively and orientate effectively, provides us creative freedom in our decision making.

Successful problem management is rooted in outcome accountability. If all the members of the Performance Team take ownership and share responsibility, then a culture of consolidation, as opposed to fragmentation, will exist.

The Performance Team

The previously discussed mental models, when well constructed and layered with outcome accountability, can help to expedite and even eliminate the decide stage. But another integral piece to the puzzle must be in place – a well designed and integrated performance team.

The process of observe, orient, decide, and act creates a feedback loop. When the right people are in place, we can tighten this loop. We can begin to uncover the signal from the noise. We can safeguard against our biases and protect ourselves from our own narratives. The unique perspectives and expertise of the individuals involved can be pooled together to determine the problem management strategies.

In essence, Ashby’s Law states that ‘only variety can control variety’ – and with the amount of variability present in the Sport Performance world, maybe having some variety within the composition of our Performance Teams is one possible solution.

So what might this look like?

How should the Performance Team be constructed?

First and foremost, we must have a team that can “play pick-up basketball”. This comes from Daniel Coyle’s book, The Culture Code, where he discusses this concept from the NAVY Seals. We must have ‘super-cooperators’. If you’ve played recreational basketball, or just about any team sport for that matter, you’ll know the importance of a team that works together in the heat of the moment – regardless of whether it is their first interaction.

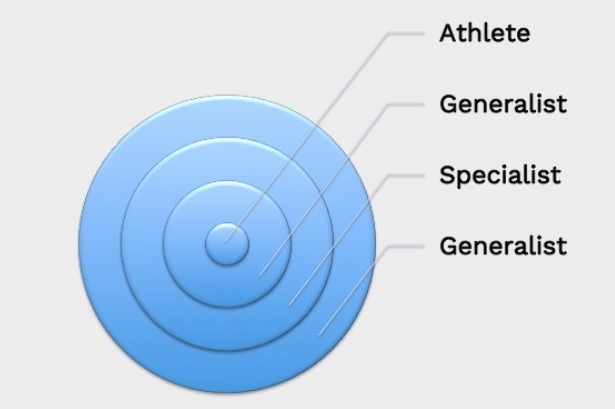

Furthermore, we need to bring together generalists and specialists, problem identifiers and solution suppliers, those who can destructively deduce and creatively induce.

With an athlete-centered model this may mean that those closest to the athlete are generalists. They are able to communicate complicated and complex topics to the athlete population. As we get further removed from the athlete we have the specialists. These individuals will often be the solution suppliers. Zooming out and looking at the big picture, tying everything together is another generalist, or Performance Director.

With this structure, and with each individual within it open to expressing vulnerability – we can begin to manage our complex problems more efficiently and effectively.