Over the last few weeks, through my weekly emails to the ALTIS Community, I have been writing about implementing a Performance Therapy methodology into an environment not currently operating in such a way. I spent a few weeks discussing the bigger problem of how to impart greater cultural change, and this week began to narrow into the details somewhat.

Motivated by the high-profile injuries in the NBA during the NBA Finals – and perhaps more specifically, the general population’s reactions to them – I write first about the complexity of health and performance in elite sport, which in my mind is the primary justification for a Performance Therapy methodology in the first place. (If this is a new term for you, be sure to read our free eBook – you can download it here.)

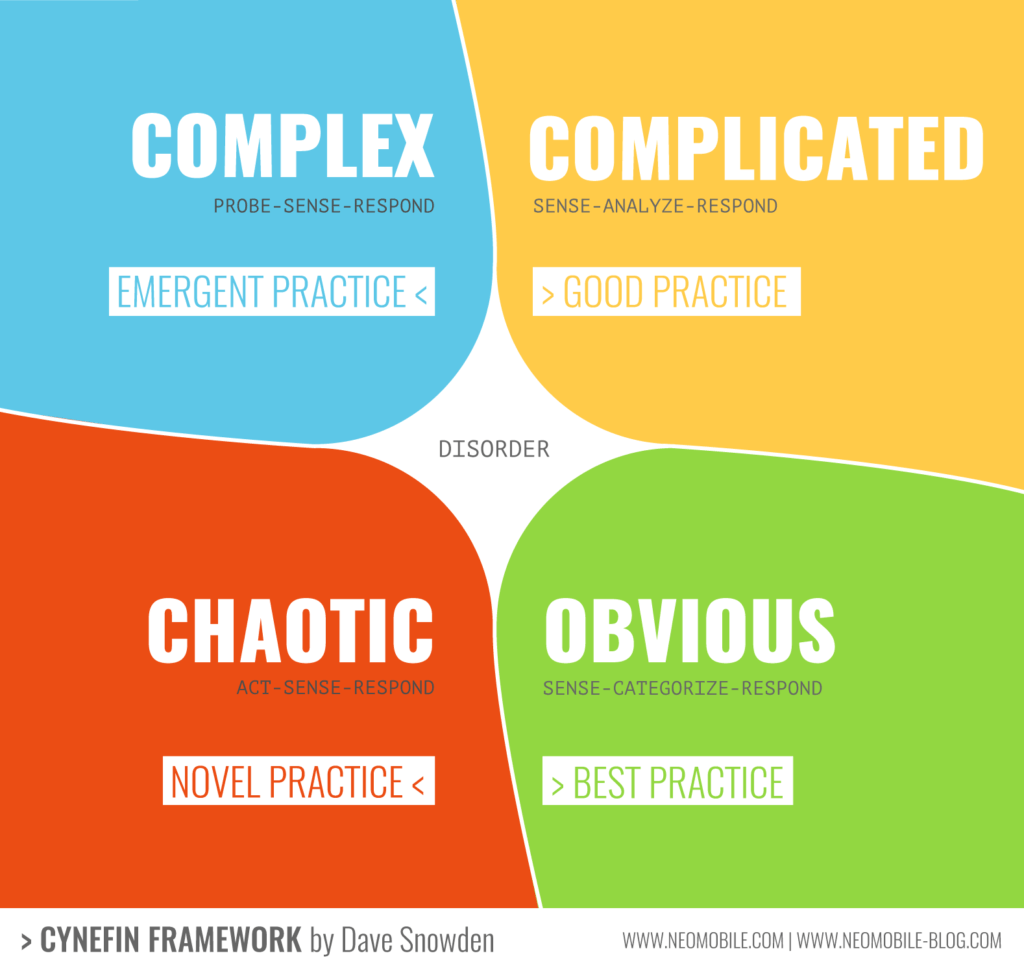

We refer to Dave Snowden’s Cynefin Framework quite often, and it has its own section in the ALTIS Performance Therapy Course. If you are not familiar with this ‘sense-making framework’, please refer to this article.

In essence, what the Cynefin Framework does is help us to make sense of different types of problems, using the degree of predictability as the determining factor. It introduces four ‘domains’ – obvious, complicated, complex and chaotic.

According to Snowden, these domains give us a “sense of place” from which to analyze behavior, and make decisions; the framework discriminates between ordered, unordered, and disordered. As knowledge expands, we can move from chaotic (no understanding of cause and effect) to complex (cause and effect only seen in hindsight) to obvious. It is important to understand, however, that we are governed by the current rate of knowledge construction; the drift from unknown unknowns (chaos) to known knowns (obvious) does not readily lend itself to complex systems – that are, by definition, complex, and cannot be reduced.

Sometimes, we simply do not have the knowledge; we must admit to this, and do our best to make decisions based on the best-available evidence, with an understanding of the iterative nature of this process.

So how do we use the Cynefin Framework in practice?

Firstly, we can differentiate human movement in a similar manner – i.e. on how predicable it is:

‘ORDERED’ (SIMPLE & COMPLICATED) movement is rare in our everyday lives, and does not exist at all in sport.

‘UNORDERED’ movements oscillate between COMPLEX (‘typical movement’* – where, in hindsight, we can discern cause & effect) and CHAOTIC (‘atypical movement’ – which begins as an unconscious movement solution (i.e. compensatory patterns we are unaware of) and leads to conscious atypical solutions (compensatory patterns we ARE aware of), and eventually DISORDER – where the movement solutions are no longer appropriate for the sporting task, a threshold is reached, and an injury occurs.

(*the cavalcade of compensations to the typical movement solution compromises our predictive abilities to the point where relationships between cause and effect are difficult to determine even in hindsight because they shift constantly and very few manageable patterns exist).

While traditional sports medicine methodologies target ORDER (non-existent) and DISORDER (injury), a Performance Therapy model focuses on the typical, UNORDERED, complex movement solutions that dominate sport, and the inherent atypical CHAOTIC variability around these solutions.

This past week, we were witness to two very high-profile examples of the complex system (and our limited ability to predict its outcomes) at work – with in-game major injuries to star NBA players Klay Thompson and Kevin Durant, both of the Golden State Warriors.

Despite what you may think you know, and what the keyboard warriors may think they know, the real Warriors’ performance team is top-notch, and I’m quite positive they made the best possible decisions they could with the information they had at the time.

They were operating within a complex – nay chaotic – ecosystem.

With the benefit of hindsight, I am quite certain that every single person involved with the decision-making process on the Warriors would have made a different decision -but we don’t get to live our lives backwards, and cannot make our decisions in hindsight.

In a complex system, all we can do is respect that often the best we can do is to gather as much information as possible, and make as good a guess as we possibly can, relative to the context of the situation.

And sometimes, we will be wrong.

In elite sport – and especially in the major professional leagues of the United States and Europe, performance teams are making decisions on “millionaire mutants” (as my friend Kelly Starrett termed them – and do not for a second underestimate the “millionaire” part in this!), and 100s of other variables – some of which we understand; most of them we don’t, as well as the interactions between them – of which we k

Too often, we bias towards some magical ‘best practice’, rather than admit to our relative uncertainty as a starting point.

Rather, we need to treat the health and performance of the athletes we work with as complex problems – employing an ecological approach that requires that we not only respect the individuality of each athlete’s solutions to their sporting problems, the bandwidth of variability around these solutions (Bernstein’s ‘repetition without repetition’), but also the practical challenge of understanding when they are outside of their typical bandwidth of variability’, potential reasons for this, and the appropriate strategies to manage this.

More to come on this in the future.

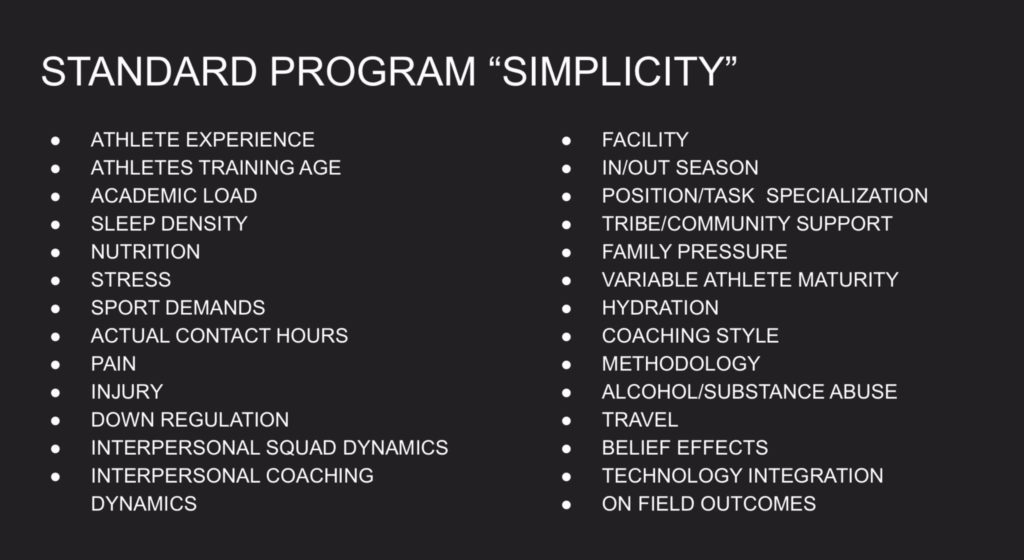

From Dr. Kelly Starrett – a very short list of some of the variables in play when making decisions in the athlete health-performance ecosystem.

I like this conclusion to a short article by Tony Schwartz from last year: https://hbr.org/2018/05/what-it-takes-to-think-deeply-about-complex-problems.

“… managing complexity requires courage — the willingness to sit in the discomfort of uncertainty and let its rivers run through us. The best practice is to not over rely on best practices, which typically emerge from our current assumptions and worldview. “In complex systems,” says leadership consultant Zafar Achi, “there is no recipe, only art.””

Tony Schwartz

If you are interested in following along on this journey into attempting to manage the complexities of health and performance in sport, sign up for our newsletter –which will also keep you up to date on the rest of the goings on at ALTIS.

Thanks for reading!

– Stu

Oh – and by the way: I’m sure by now you have heard that we have dropped the price of ALTIS 360 down to $9.99/month. I am somewhat biased, but this is an absolute steal! It has been our goal from the outset to get into a position where we can offer our video portal at a price that everyone can handle. And finally – 3 years after launch – we have been able to do so. There’s never been a better time to sign-up: for less than 2 lattes a month, you can enjoy 100s of hours of video from us, and all our smart friends in sport.

If you already subscribe – awesome! Thanks for your support – and maybe you have a friend who would be interested? If you’re not already a member – what are you waiting for? Subscribe now!