In sprint biomechanics, we can quite easily get caught up in the minutia.

Ground contact time, flight time, step length, step frequency, stiffness, momentum, acceleration, peak velocity, average velocity, thigh angular velocity, toe-off angle, touchdown distance … the list goes on.

It can quickly become overwhelming – so I totally understand the nature of many of your questions as they relate to Motion IQ. It may seem like you need to have a PhD in biomechanics to understand things.

But our goal with Motion-IQ is not for you to become an expert sprint biomechanist. Our goal is to help you better understand what the sprint biomechanics data says about the players you coach, and how you can use this information to help them run faster.

Pretty simple, right?

Well – not really. Not when you’re talking about all of these extremely complex data points that all interact with each other in very complex ways. But in this interaction lies the secret to better health and performance.

It's called a whole-body strategy, and it’s the next evolution in health and performance [yes, I know that sounds a little overly-enthusiastic, but I mean it!].

So what’s a whole-body strategy?

In the context of an athlete's sprinting performance, a whole-body strategy implies a holistic approach to analyzing and understanding how an athlete's entire body coordinates, communicates, connects, and controls during sprinting.

“[Sprinting] … is a complex, whole-body movement that requires the coordination of multiple interacting components in the ‘kinetic chain’” – Dr. James Wild, 2024

Instead of focusing on isolated body parts or movements, a whole-body strategy considers how all parts of the body work together in an integrated manner to produce an individual athlete’s most-efficient movement pattern for sprinting.

In short – through utilizing higher-level spatiotemporal characteristics [contact time, flight time, step length, step frequency, velocity, and leg length], we can better understand each individual athlete’s sprinting strategy – i.e. what works best for them!

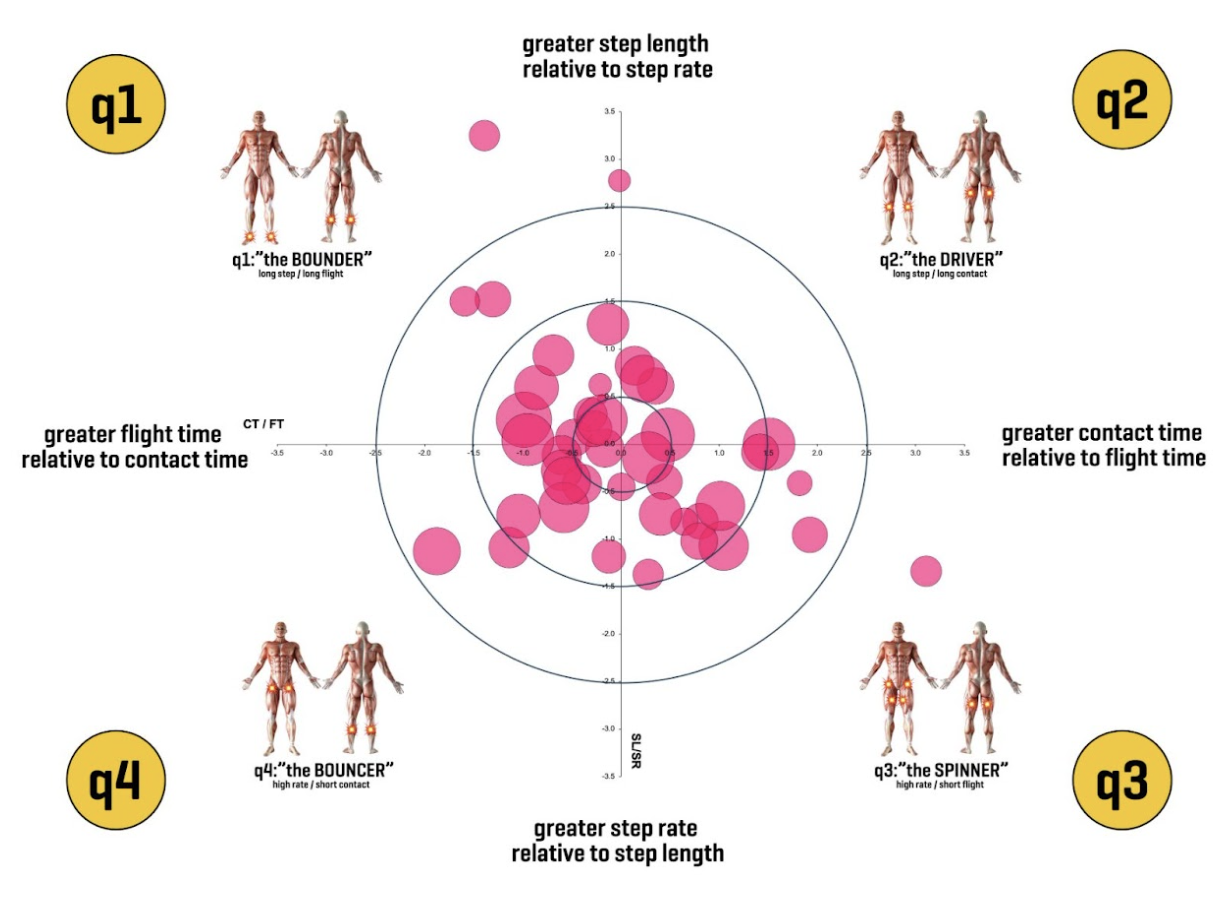

This is what an example of such a strategy looks like in practice with a group of NFL player [each pink circle denotes one player, and the bigger the circle, the faster the player]:

Pretty cool, right?

If you don't understand what this means – don’t worry, I’m going to go into it at some length over the next few weeks. It’s super-fascinating and powerful stuff!

Identifying sprinting strategies with this holistic whole-body viewpoint provides a rich source of information that considers the ‘system behavior’ of the athlete as a totality. This contrasts with an averagerian approach, where all athletes are taught the same biomechanical model, or an overly-detailed, reductionist approach that might focus on more granular, isolated metrics that do not capture the integrated nature of the movement.

“Group-based analyses often mask variability between athletes and only permit probabilistic ‘in general’ or ‘on average’ statements that may not be applicable to specific athletes.” – Glazier, 2019

Ultimately, the whole-body approach can help in establishing whether there are distinct, effective strategies within a group of athletes, which could influence training and therapeutic methods. If certain strategies are associated with better performance, training could be adjusted to promote these more effective patterns.

And, if no single strategy stands out, then personalized training interventions might be necessary to enhance each athlete's individual sprinting performance.

But I’m getting a little ahead of myself here.

Let’s rewind a little.

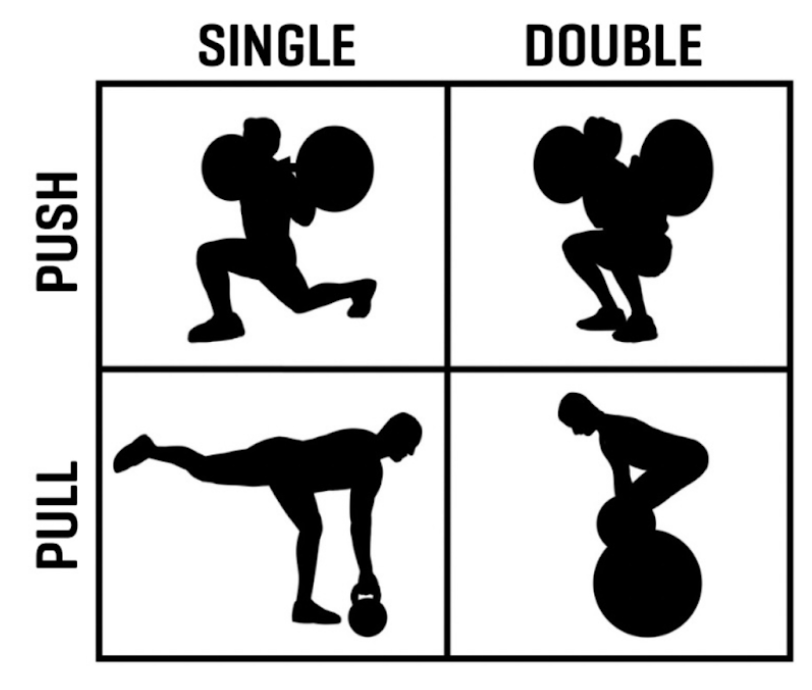

I’ve been working on my own version of a ‘whole-body strategy’ concept for a couple of decades. You might be familiar with my pusher / puller – double-leg / single-leg classification [Figure 2]. This is a rudimentary version of what has now been taken much further – and with much greater accuracy by people much smarter than I.

This classification effectively details whether an athlete is single or double-leg dominant, and whether they are posterior-chain [pull] or anterior-chain [push] dominant.

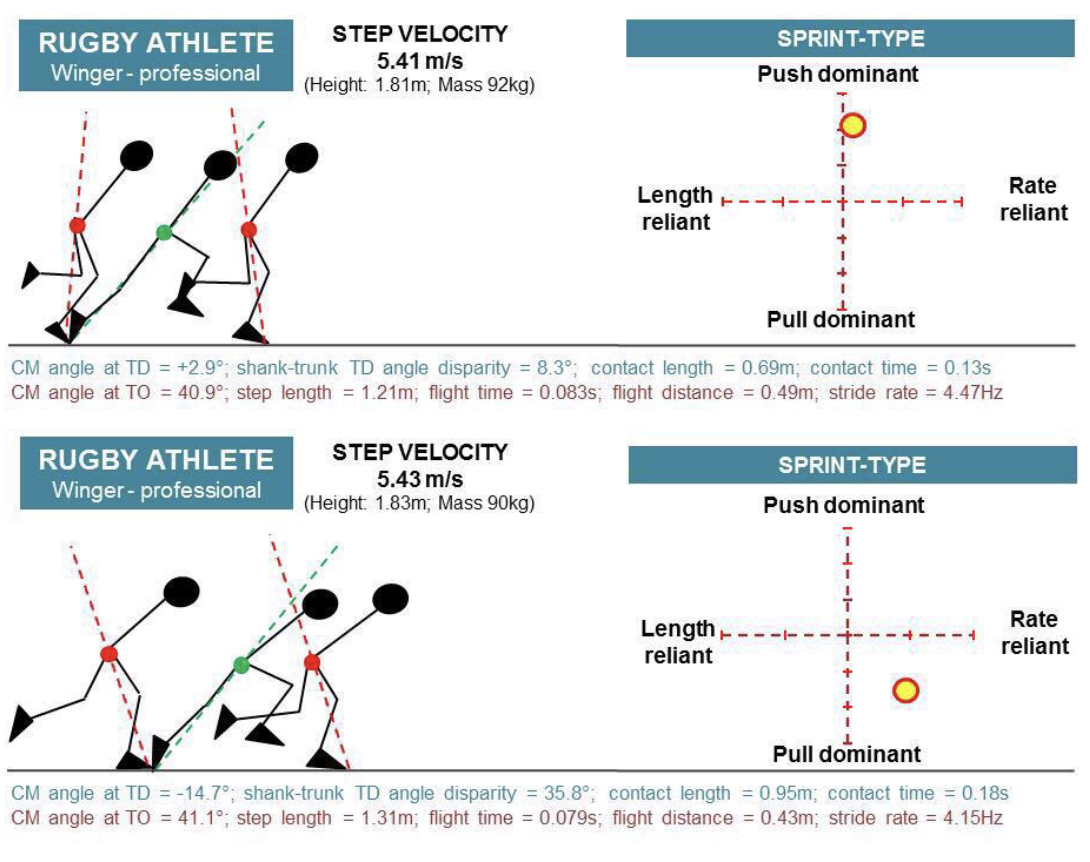

My friend James Wild in 2014, expanded on my push-pull categorization by adding in information that determined whether athletes were more reliant on step-rate for their speed, or step-length [this addition was influenced by Aki Salo’s work. I highly recommend reading this great paper]. This served to form a really powerful dual-axis framework, where James was now able to identify a player’s strategy as biased towards one of four options.

- Push & Step-Rate

- Push & Step-Length

- Pull & Step-Rate

- Pull & Step-Length

Adding whether an athlete relied more on step rate or step length for their speed was a great addition, and really added some objectivity to my original classification.

What do you think?

Have you heard of a whole-body strategy before? If you have, have you been applying one with your athletes and teams? If you haven’t, how would you use this type of information to inform your training?

I’d love to hear from you.

Next time, I will show you how we have been doing it more recently, and how all of this is being implemented into the next Motion-IQ linear sprint update.

Thanks for being here.

P.S. Have you checked out Rich Clarke’s COD-Braking Report yet? It’s the newest Motion-IQ product, and if you work in team sport – it’s a must-have.

Rich is my go-to guy for all things COD and braking. You might have read some of his work, or familiar with his socials? If not – and even if so – you should check out some of his writing. Start here, with this: (PDF) Phases of the traditional 505 Test: between session and direction reliability. (researchgate.net)

ENJOYED THIS POST?

SIGN UP FOR OUR FREE WEEKLY NEWSLETTER - HOW WE MOVE - and get weekly insights into movement for team sports.