Written by Mohammad Nourani — current intern coach at ALTIS and former NCAA collegiate athlete.

Every Ramadan is said to be unique, and 2020 is no exception. The current global pandemic has added additional hurdles for Muslim athletes, who now have to find even more creative ways to train, on top of dealing with the challenges of Ramadan. Not that long ago, the subject of athletic performance during Ramadan was in the spotlight of professional sports. Enes Kanter, basketball center for the Portland Trail Blazers, was vying for a championship with his team in the 2019 NBA playoffs, while openly observing Ramadan. For him, this meant partaking in practices, team activities, and sometimes games while fasting1. Kanter has been candid about his faith and how it relates to sports throughout his career, and has become a role model for many Muslim athletes around the world.

Athletics and Ramadan come to clash once every year: tens of thousands of athletes around the world continue their training — in some cases even competing — while engaging in the various cultural, religious, and social activities that Ramadan represents for them. Now, the condition an athlete comes out of after this month depends largely on their own and their coach’s preparation, mindfulness, and flexibility. Along with the substantial amount of research done in this area, plus my own experiences, I was fortunate enough to be able to discuss the topic of training in Ramadan with several elite athletes and coaches (bios at the end of this article).

Introduction to Ramadan & Athletics

Ramadan is a holy month in Islam, which has nearly 2 billion followers worldwide. Ramadan is also a time for family and social activities centered around prayer and/or faith. It is a remembrance of the time when the Quran was first revealed. Philosophically and aside from the rituals, fasting is a platform for Muslims to abstain from ordinary pleasures and focus on gaining self-control, piety, humbleness and seek a stronger relationship with their Creator. For about 30 days, Muslims all over the world will fast from dawn to sunset, which means no food or water for approximately 12-18 hours (depending on one’s geographic location). Muslims will usually wake up before to dawn for the pre-fast meal, called Suhoor, which is eaten prior to the first prayer of the day (~ 3-5AM). The purpose of Suhoor is to provide some amount of lasting energy and hydration for the long day of fasting that lies ahead. At dawn the fast has commenced, and is not to be broken until nightfall (can be ~7 to 9PM). This evening meal that breaks the fast is called Iftar.

The Islamic (Hijri) calendar follows the lunar cycles, meaning that each new moon represents the start of a new month. Ramadan is the ninth of twelve months in the Islamic calendar. The Gregorian calendar, followed by most of the world, is based on the Earth’s rotation around the Sun. As a result, the month of Ramadan does not fall at the same time every year in the Gregorian calendar. Every calendar year, Ramadan will begin roughly 10-15 days sooner than the year prior.

Although the effects of Ramadan fasting are minor on generally sedentary populations, for athletes, these effects are heightened. Training during this time presents particular challenges, regardless of the sport (as if it isn’t taxing enough under normal circumstances). During Ramadan, some may adjust their training to allow for extra rest, while aiming to maintain the skills, strength, and fitness that they have already built. Others may fast on and off, to stay sharp and healthy in their careers, while still expressing their faith. But, the majority of athletes and their coaches will agree: the athletes can’t just do nothing. They cannot afford to lose the fitness/skills they have developed up to this point by taking 30 days completely off. Moreover, we have seen many cases throughout history when important competitions have fallen during Ramadan, such as the 2012 Olympic Games2. Competitive fires won’t die out simply because of physical hunger or thirst.

Before diving into the specifics, it is crucial to understand the pivotal roles that culture plays for Muslim athletes and Muslims in general. Observation of Ramadan is quite different in places like Europe or North America, versus predominately Muslim nations, such as those in the Middle East or Africa. In areas of the world where Ramadan is more commonly practiced, society as a whole makes temporary adjustments to how they live. For example, restaurants and cafes will not serve food or drink until sundown, but will have longer hours after dark. Businesses might give their employees a temporary schedule for the month, so that they can avoid hardships associated with fasting. In such cases, coaches, teams and/or groups of athletes might have an easier time in adjusting the various aspects of their training, as they have the backing of the society around them.

Conversely, athletes in mainly non-Muslim areas face additional roadblocks, particularly in team sports. Coaches are less likely to adjust the entire groups’ training when the circumstances of Ramadan are only presented by a small minority of the team. Being a minority on a team or in a training group, Muslim athletes might also face the social stigma that comes with asking to sit out or have easier workouts, especially in youth sports. As a result, many learn to just push through hardship for a month, and year after year, they wind up practicing and competing in both team and individual sports while in a fasted state.

Is that ideal? Probably not. Still, athletes across the globe have shown time and again, Ramadan training can be done. And more importantly, it can be accomplished optimally.

For those new to Ramadan training, I believe the biggest point to understand is that the challenges presented to a fasting athlete are multifaceted — not just nutritional. Key Ramadan training considerations include scheduling, adjustments in training design, recovery/sleep, motivation & mental state, and of course nutrition. Even normally, these factors should be considered interdependently; their collective value is perhaps amplified even greater during Ramadan.

Scheduling – Day to Day

Ramadan is a complete, ~30 day, lifestyle change for the majority of observing Muslims. As such, successfully modifying everyday schedules is arguably the most important of the considerations. Though this is obviously not ideal, adjustment is necessary to help athletes get through training given all other Ramadan factors. For observing athletes, there are options when it comes to the day-to-day routines, regardless of location. According to Tom Crick, Head Athletics Coach at Aspire Academy in Doha, Qatar, there are two go-to strategies for their coaches and groups during this time. The first, perhaps with the least strain on the body, is to delay training until after Iftar. That way, the athlete is able to eat a light amount pre-workout, hydrate during exercise, and properly refuel post-workout. The second, is to train while fasted just before sundown and properly refuel and rehydrate when finished3.

Some other methods could include training in the remarkably early morning hours, prior to Suhoor, or simply training at regular times, but in a fasted state. Both of these are very possible, but each also presents complications that are not ideal for athletes. The former would mean that an athlete must either wake up ridiculously early (as early as 3am) and workout, or remain awake throughout the night and essentially become nocturnal, which would have its own issues. On the other hand, exercise in the early hours of the day, whether fasted or not, may have an added benefit, as muscle glycogen stores will not be as depleted as they will be at the end of a day of fasting.

As for the latter, training completely fasted and staying fasted afterwards for the remainder of the day can be quite uncomfortable for some. It may be difficult to go on with the rest of the day feeling tired, dehydrated, and hungry every day for 30 consecutive days. Nevertheless, athletes in non-Muslim areas may have no choice if they wish to continue training with the group during this time. Even if fasted, many athletes like Olympian Hafsa Kamara, prefer group training over solo workouts. She adopts a Ramadan routine that is as close to the other 11 months of the year as possible4. Though it still takes a bit of time, less total variation can shorten the adjustment period.

Planning for scheduling changes in Ramadan training is crucial. For observing athletes who are new to Ramadan training, experimenting with training timings prior to the beginning of Ramadan might be a good start. This will reduce some of the ‘shock’ when fasting begins. Consider chronotype (e.g. ‘morning person’ or not), and find a time that will work for the athlete and does not result in additional mental or physical strain. If training times cannot be changed due to preference or team requirements, communication with coaching staff before Ramadan is of utmost importance. Regardless of what time of day is selected, adjusting to a new routine will take a few days, and should get easier with time. Coaches should be mindful of the drastic shifts in an athlete’s life during this time, especially if an athlete is training while fully fasted. Tracking progression or regression can also be helpful in determining further training modifications.

Competing

Competition scheduling is a different story. As previously mentioned, Ramadan does not fall at a uniform period in the Gregorian calendar. Because of this, it is very possible that Ramadan could fall ‘in-season’ for any sport during a given year.

Thus, depending on when Ramadan falls in the Gregorian calendar each year, athletes will have to make unique adjustments. Probably the most ideal situation for an athlete is for Ramadan to be during the ‘off-season’ of their sport. That way they can observe fasting and train, without the added pressure of competition. Despite any careful planning, the fact remains that the majority of sports, especially in non-Muslim nations, do not make allowances for Ramadan. Take 2019 for example: the Gregorian calendar dates for Ramadan were May 5th – June 3rd. In Track & Field alone, that was the height of the high school/collegiate seasons in America, and it was the beginning of competitions for many pros on the domestic and international stage. A few other major sporting events outside of Track & Field that took place during Ramadan 2019 were: the NBA Playoffs, Roland Garros, and the UEFA Champions League Final5. A competitive athlete would not want to miss out on participating in such important events; this is what they train for.

So in the event that Ramadan falls in-season, what can be done? Ultimately, a decision has to be made by the athlete and coach, and it should be made as far in advance as possible. Choose to compete, choose to fast, or do both in some capacity. There are athletes that choose to avoid competitions during Ramadan, so they should work with their coaches and note the days prior to beginning their competitive season. Others will attend events and compete without fasting, and choose to make up the days missed later in the year. The 2014 FIFA World Cup featured a number of Muslim footballers who publicly stated their intent to break their Ramadan fasts during the tournament, citing livelihood reasons6. Few athletes, especially at the elite levels, will decide to compete while fasted. But that does not mean fasting and competing cannot be done simultaneously — Hakeem Olajuwon was praised for his incredible performances, matching and even surpassing his output in the rest of the season, while observing Ramadan in the 1990s7.

Training Design

The majority of the early research done regarding the effects of Ramadan fasting showed that athletic performance indicators, in particular anaerobic power, anaerobic capacity, aerobic power, and muscle strength, were adversely affected. 8

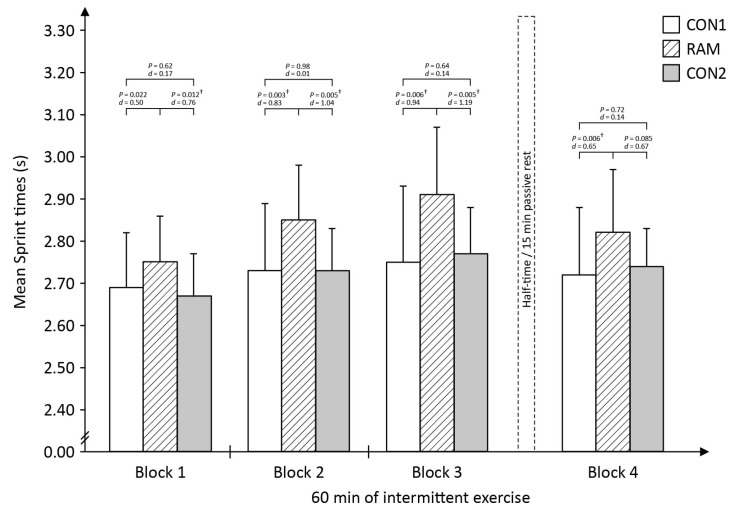

More recently, however, numerous studies have shown that by appropriately controlling consistent training, sleep, diet, and fluid intake, the declination in performance can be reduced to minor levels, or no decline at all in some cases 9. If performance does depreciate slightly during Ramadan, however, in almost all cases it tends to go back up afterwards. The figure below shows that although sprint times were consistently slower during Ramadan (RAM) than in the baseline (CON1), the times became faster again after Ramadan (CON2) 10.

In response, many coaches and athletes will go into maintenance mode during Ramadan. This is not necessarily a bad move, because it allows for built qualities to be preserved, and likely eliminates some of the injury risk. The number of weekly sessions, or the volume per session, may be reduced to allow for increased recovery time in response to Ramadan lifestyle changes. Many affected training groups have acknowledged this fact, dropping the number of weekly sessions by two or three, depending on the athlete3.

But Adi Vase, Performance Coach of the Golden State Warriors, argues high intensity work should not be totally neglected during this time, especially in speed/power sports or events. “Avoiding high intensity work will have consequences for post-Ramadan, as an athlete tries to build back up to manage a high training volume. I’ve experienced a few instances where athletes avoided all high-intensity work during Ramadan, and actually got injured in the 2 week window following Ramadan as they tried to ramp back up too suddenly.” A sprinter, for instance, who does not sprint for 30 days will not be feeling very explosive at the end of it, and will put themselves at risk if they try to jump back into high intensity efforts right after Ramadan. Instead, Vase recommends keeping the body in touch with high intensity stimuli related to the sport, but reducing the volume. “Strategies I’ve used in the past include cutting down both reps and sets as well as making good use of cluster sets in training programs” 11.

One prevailing question: can new heights be reached during Ramadan? The uninspiring answer is: it depends. But trying to hit PRs in the weight room or track should be approached with extreme caution. Rather, Ramadan circumstances might be a great opportunity to focus on improving skill work. These sessions can be mentally and neurologically stimulating for athletes, and ‘gains’ in technique or fluidity of movement can be made, with less global fatigue.

Preservation of fitness and skill during Ramadan will require changes from the normal training design. Flexibility with scheduling is key. Again, it needs to be understood and respected that there are numerous variables facing fasting athletes that can affect the quality of their training. The common traps to avoid falling into are (1) not adjusting plans at all, leading to overtraining and injury risk in a time of great change, or (2) winding up doing 30 consecutive days of low intensity, low quality training. A happy medium between these two may be the best bet: maintaining close to the level of ability that had been built up to that point, but not actively pushing to reach new levels. If fatigue is accumulating, consider perhaps a momentary shift to skill-centered training. Most importantly, keep in mind that these changes are temporary.

Sleep

Sleep during Ramadan is tricky, especially in parts of the world where Islam is not widely practiced. Iftar is at sundown, and for many that is later than their usual ‘dinner’ hour. The time post-Iftar is typically used as family or prayer time, so going to bed immediately after eating is not common. Bedtimes wind up being later during Ramadan than the rest of the year, resulting in less overall sleep. To compound this, waking up early for the Suhoor meal interrupts the normal nighttime sleep, and going back to bed afterward on a bloated full stomach can be difficult. Even if a post-Suhoor nap is successful, it might not be for very long. In places such as the United States and Europe, career and academic schedules do not change during Ramadan. For most Muslims in these areas that means they have to be up and functioning again by 7-8 in the morning. As a result, daytime sleepiness is quite common during Ramadan12.

The lack of sleep and altered circadian rhythm can lead to a plethora of issues for athletes, such as hormone imbalances, immune system weakening, gastrointestinal issues, and an overall increase in fatigue. Although, like many aspects of Ramadan, sleep schedules also get easier as the month carries on. In my experience, it takes about 7-10 days to fully adjust to new Ramadan sleep patterns, considering also the timing adjustments made in training and food intake.

But the holy grail of eight hours of sleep per day is still achievable, and fasting athletes should strive to get as much sleep as they can between Iftar and Suhoor. Sleep after Suhoor may be difficult due to academic or career schedules, and should not be heavily relied on. Short naps after Suhoor or during the day also have been shown to help with fatigue, but long naps can further disrupt night sleep. Like travel time zone changes, it may be beneficial to the athlete to begin the new sleep regimen prior to the start of Ramadan.

Nutrition

Throughout a day of Ramadan fasting, physiological changes in all populations include decreases in blood glucose levels, muscle glycogen, and bodily fluid reserves. Although there can be some health benefits to fasting intermittently, mainly in sedentary populations, the effects on competitive athletes are not universally accepted. Most people unfamiliar with Ramadan fasting would think that nutrition is the biggest factor. While it has substantial value, having one less meal a day and no snacking might not be a disaster situation, after all. This is demonstrated in the popular weight loss diet regimen of intermittent fasting. Competitive athletes likely do not want to be losing or gaining weight rapidly, but with a few tweaks, energy intake can still be adequately maintained during Ramadan fasting, but perhaps with more difficulty than when not fasting.

While it is very important to eat sufficiently to make up the fuel deficit, meals should still be as well balanced as possible. Breaking fast at Iftar commonly means overeating, since the long day of fasting has led to steadily increasing hunger. Self-control right at the point of Iftar can go out the window. Chronic overeating can lead to digestive issues, and further affect sleep. Another common trend is not eating/hydrating enough during Suhoor to sustain one’s body for the day, especially if they will be training while fasted. Some athletes may even opt to skip the pre-fast meal in favor of more sleep, but it is crucial to have some sort of lasting energy for the day.

Weight loss or weight fluctuation during Ramadan is common in athletes, and perhaps inevitable to some degree. This too can be outlined in advance and mitigated. Professional hurdler Evonne Britton looks to add significant calories to her diet in the weeks leading up to Ramadan. “I want to have more to give….my body’s going to be shocked [anyway], so I might as well give it a little bit of a cushion” 13. In this way, the impending weight loss from fasting has a smaller net effect.

Overall, aim to keep nutrition as close to what it would be outside of Ramadan. Over-analyzing what is being consumed during this time will only add an additional stress to the athlete. Again, minor changes in performance or weight are temporary. If there is a true deficiency in any macro-nutrient, that can still be addressed with supplementation.

Mental/Emotional State

In my opinion this is the aspect of Ramadan that can affect training quality the most, and not just from a ‘mental toughness’ standpoint. Besides the physical changes, Ramadan affects different people in different ways mentally too, with feelings of extraordinary fatigue and lethargy being the most common, as well as an increase in the perceived level of exertion14. Alertness and concentration were also shown to decrease throughout the day while fasting, one study showing an increase in daytime traffic accidents during Ramadan.15 Mood changes, likely due to the reduction in blood glucose during a fast, can lead to a lack of motivation to train or compete. Think about it: as a 16 hour day of no food or water progresses, who wants to even think about working out? I probably spend half the day thinking about what I’m going to eat for Iftar.

The mind, whether consciously or subconsciously, has complete control over the body. A 2017 study by Aziz et. al concluded the main culprit for decreases in sprint performance during Ramadan was the Nocebo, or “imaginary” effect. (10) Basically, because the athletes believed that their performances would decline due to them feeling tired, hungry, or thirsty, the results were exactly that.

Both athletic performance and fasting by elite athletes during Ramadan are to some extent determined by the brain and its ability to push past a certain limit. Basketball player Batouly Camara says, “There are two thoughts that help me. The first is that Allah knows why I am doing this and I know the reward is greater than this temporary struggle. The second is for those [Muslim-athletes] who will come after me. I want them to be able to have a conversation with their future coach and say ‘I am a Muslim and I will be fasting,’ with no negative thoughts to follow.” 16

We have to respect the power that the mind has over the body, and that Ramadan fasting may lead to various psychological complications that can have effects on training quality. But also understand that the solution is not as simple as ‘being tough.’ This is again where planning and physical preparation in advance of the start of Ramadan can make a considerable difference. Taking care of seemingly unrelated things such as nutrition and sleep can have a major effect on fatigue, mood, and motivation.

Concluding Thoughts

For those who’ve made it this far, I applaud you. From my journey through experiences, research, and testimonies from elite athletes and coaches, I believe that training while observing the month of Ramadan is very do-able, if coaches and athletes understand the obstacles, plan, and are adaptable.

My top tips:

| Actions | |

| Schedule | Athletes should plan for Ramadan as far in advance as possible, and communicate this with coaches & teams Coaches need to be mindful of the major challenges Ramadan presents to athletes, and be flexible Coaches and athletes together should note any competition dates that may fall during Ramadan and discuss plans to either partake or abstain. Whether training just before/after Iftar, prior to Suhoor, or during the day as normal, try to explore different timing possibilities. Decide what sort of schedule will work best given the circumstances. If possible, athletes should try to acclimate to the new routine 1-2 weeks prior to the start of Ramadan, so their bodies are not shocked when it begins. |

| Training | Though athletic performance might decline somewhat, regular training is still needed to maintain fitness and skill Be flexible in training design, and realize that ‘Plan B’ options might have to be relied upon more than they normally would. High intensity efforts should be carefully controlled in volume and recurrence, but not avoided altogether |

| Sleep | Athletes should aim for at least 8 total hours of sleep per 24 hours. Small naps can be taken to negate additional fatigue, but don’t rely on naps too much |

| Nutrition | During both Suhoor and Iftar, be sure to refuel and rehydrate adequately. Try to keep meals as balanced as possible Supplementation can be used to combat any major deficiencies. |

| Mental | Motivation, perceived exertion, or confidence in the sport can vary in response to Ramadan lifestyle changes Solution is not as simple as ‘getting tougher.’ Be wary of overexerting athletes with so many other stressors in place Keep in mind that whatever physical, mental, or lifestyle changes that occur during this time are temporary |

Elite athletes throughout history have shown that with proper preparation, quality training and even competing during Ramadan is an achievable feat. As Ramadan 2020 comes to an end, I’d like to wish an early Eid Mubarak to everyone. In the difficult times this pandemic has brought forth, let’s remember how resilient and strong humans can be. Stay safe, keep calm, and sports will return.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank those who shared their insight and experiences for this feature.

- Evonne Britton, Adidas professional sprinter and hurdler

- Batouly Camara, former University of Connecticut Division 1 basketball player

- Lee Christopher, Lead Sprints and Hurdles Coach at Aspetar Academy in Doha, Qatar

- Thomas Crick, Head Athletics Coach at Aspetar Academy in Doha, Qatar

- Hafsa Kamara, 2016 Olympian and professional sprinter

- Adi Sam Vase, NBA Performance Coach with the Golden State Warriors in San Francisco, California

References

- Kanter, Enes. “What it’s like to Fast for Ramadan While Competing in the NBA Playoffs.” The Washington Post. 2019 May. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/05/09/enes-kanter-when-ramadan-nba-playoffs-collide-my-faith-is-my-strength/

- Borden, Sam. “Ramadan Poses Challenges for Muslims at the Olympics.” The New York Times. 2012 July. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/01/sports/olympics/ramadan-poses-challenges-for-muslims-at-the-olympics.html

- Virtual Q&A interview with Tom Crick. Zoom call. 4/29/2020

- Virtual Q&A Interview with Hafsa Kamara. Zoom call. 5/9/2020

- “Sporting Calendar 2019: Major events of the year.” BBC Sport. 2019 November. https://www.bbc.com/sport/46484421

- Gjorgievska, Aleksandra. “Muslim World Cup Players Weigh Options for Ramadan.” TIME. 2014 June. https://time.com/2933705/world-cup-ramadan/

- Khan, Monis. “Hakeem Olajuwon’s Five Most Impressive Ramadan Performances.” The Undefeated. 2018 May. https://theundefeated.com/features/hakeem-olajuwons-most-impressive-ramadan-performances/

- Shephard, Roy J. “The Impact of Ramadan Observance upon Athletic Performance.” Nutrients. 2012 Jun; 4(6): 491–505. Published online 2012 Jun 7. doi: 10.3390/nu406049. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3397348/

- Maughan RJ, Zerguini Y, et al. “Achieving optimum sports performance during Ramadan: some practical recommendations.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2012;30 Suppl 1:S109-17. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.696205. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22769241

- Aziz A, Muhamad A, et al. “Poorer Intermittent Sprints Performance in Ramadan-Fasted Muslim Footballers Despite Controlling for Pre-Exercise Dietary Intake, Sleep and Training Load.” Sports (Basel). 2017 Jan 6;5(1):4. doi: 10.3390/sports5010004. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29910364/

- Figure: Players’ mean 15-m sprint times during the modified Loughborough Intermittent Shuttle Test (mLIST) exercise in the non-fasted or control (CON1 = before Ramadan month, CON2 = after Ramadan month) and Ramadan-fasted (RAM = in the Ramadan month) exercise trials (N = 14). † Post-hoc significant differences, P < 0.017.

- Virtual Q&A Interview with Adi Sam Vase. Google mail.

- Taoudi Benchekroun M, Roky R, Toufiq J, et al. “Epidemiological study: chronotype and daytime sleepiness before and during Ramadan.” Therapie 1999;54:567–72

- Virtual Q&A Interview with Evonne Britton. Zoom call. 5/8/2020

- Chennaoui M., Desgorces F., et al. “Effects of Ramadan fasting on physical performance and metabolic, hormonal, and inflammatory parameters in middle-distance runners.” Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2009;34:587–594. doi: 10.1139/H09-014.

- Roky R, Houti I, Moussamih S, et al. “Physiological and chronobiological changes during Ramadan intermittent fasting.” Ann Nutr Metab 2004;48:296–303

- Virtual Q&A Interview with Batouly Camara. Zoom call. 5/1/2020