Carefully considered training progressions underpin long term planning strategies, and are a requisite for improvement over time; but what does ‘progression’ really mean? ‘Progression’ or ‘progressions’ is often labelled synonymously as ‘Long Term Athlete Development’ (LTAD) in the literature. However, in our opinion, the term ‘LTAD’ has become a bastardized one. In some people’s minds it means something very specific, and in others it is a catch all for youth development. We have therefore deliberately stayed away from it. This is also why we have avoided advocating specific, rigid, methods and means of progressions for this module.

Our aim is instead for you to learn the principles which will equip you to to create your own pathways or systems; not for us to tell you specifically what to do with each individual exercise. We want to arm you with knowledge to create your own development progressions, in your own environment.

WHY IMPLEMENT PROGRESSIONS?

The correct implementation of progression in a training scheme results in three key outcomes:

First, it ensures that the long-term loading placed upon an athlete is appropriate and progressive; helping to avoid sudden, intolerable increases in load (volume and / or intensity).

Second, it means that the appropriate type of work is performed when it should be. This means specialized workloads are performed at a stage when athletes are most prepared to accommodate, and make the most of that particular stimulus. This is not just about avoiding introducing the wrong types of work too early (i.e. specializing too early), it is about ensuring an athlete is mature enough to take advantage of the exploitation of specialized training modalities (such as maximum or specific strength training, for example) at the right time. The timing of the introduction of such specialized training means such as these is critical; the better mistake is in fact to be too late, rather than too early with their inclusion into a program.

Third, progressions create balance in programming (this balance is both short term and long term). For instance, correct progression patterns in programming ensure that there is a holistic distribution of movement patterns across a timeline, and that unidirectional and specific movement patterns are not over-prescribed to athletes before they are capable of tolerating such loads.

PROGRESSION PATTERNS – CLARIFICATION

Before we move on, let’s explore the term ‘progression patterns’ in more detail. The reality is, it can refer to a few things:

1) The objective chronological evolution of performance of a single athlete, or a group of athletes over a period of time. This is often described graphically using records or rankings, or relating to specific ages. For example, the ranking of a tennis player across a number of years, or 400m times for a swimmer according to their age.

2) The physiological, biomechanical, and psychological development driving competition trends and results over a period of time. For example, the changes in VO2 max or body fat for a distance runner over a period of years; or the step / stroke length, and frequency a runner or swimmer exhibits through their career.

3) Alternatively, it could refer to subjective evaluations – for example, the level of self-confidence, anxiety, time perception accuracy, etc., for a given athlete.

What a progression pattern looks like will very much depend on the population and specific sport being observed; so both the comparison of general sport trends, and individual athlete trends are monitored to provide patterns. This monitoring is critical, as it gives us clues on the direction training needs to take to increase performance results. It also helps us to minimize the inevitable performance drop-off which occurs for Masters level athletes as they mature.

LONG & SHORT-TERM PROGRESSIONS – AN OVERVIEW

The implementation of short-term progressions is critical for short to medium-term peaking and form attainment across an annual plan. Short-term progressions rely on the continuing manipulation (or cycling) of variance and load (volume, intensity & density). Doing so develops an athlete’s movement and physical literacy abilities from general to specific, or lack of ‘form’ to ‘form’ attainment.

The selection of rational and systematic loading strategies is critical in determining the efficacy of the development of any targeted motor ability. For example, the exact characteristic of speed progressions (i.e. the introduction of the various types of speed abilities) has a large impact on how an athlete peaks, and when peaking will occur. Likewise, the systematic implementation of the various forms of strength development modalities strongly impact how various strength qualities are transferred to the competitive event.

When working with developing athletes, a common mistake is having too narrow a mindset and short term perspective without consideration of the global view. This may lead to a rapid progression in short term performance – which although acutely gratifying – will be detrimental to long term progression. Remember: Athletes are supposed to peak in their 20s, not in their teens!

LONG TERM PROGRESSIONS

Long term progressions rely on the step-by-step introduction and development of key abilities over time in order to create a stable base for the future. This base provides a platform from which to allow a maximal exploitation of specialized abilities in the senior ranks.

Understanding the precise high performance demands for a given sport is therefore critical for a development coach designing long term progressions, as one of the key jobs of a development coach is to prepare athletes for high performance training!

As this long term journey will usually be conducted by more than one coach, this also puts a certain responsibility and obligation onto high performance coaches to work with development coaches and educate them. This is one of ALTIS’ core beliefs: We should be seeing high performance centers opening their doors and welcoming development coaches into their environment. It benefits our sport as a whole, as well as the athletes feeding into high performance programs.

COACHABILITY

An athlete who is the product of an effective long term progression pathway, orchestrated correctly by all coaches they have worked with, is deemed what we term “coachable”: That is, they enter high performance training in a state that allows the high performance coach to begin (or gradually continue) the process of specialized training, without delays and interruptions.

Athletes who enter into a high performance environment without a stable base of preparation, or with chronic injury histories may instead require years of corrections by the high performance coach. This can erode valuable resources in terms of time and energy at a critical phase in an athlete’s high performance career window.

So how can we define how effective a development coach is with their choice of long term progressions? The answer lies in the response to some key questions…

- Are the athletes in the development program improving and achieving success?

- Did the athlete stay in the sport long enough to actually make it to a high performance training environment? Or is the athlete hurt, burned out, and ready to quit by the time they reach this level?

- Is the athlete coachable – i.e. do they have enough resources left to allow room for development?

- Are they primed for the beginning of maximal exploitation in the key areas?

For example, let’s consider an athlete joining ALTIS at age 21 – if they’ve already been training maximal strength and intensive special endurance for years, we are left with very little to work with. What we really want is an athlete to enter this environment with strongly developed mechanics – in key areas of technique – while possessing a good base of preparation across motor abilities. So – for example, they have an understanding of correct technique in modalities such as the Olympic Lifts; good general speed and strength qualities; they are versed with an understanding of their sport; and they are emotionally ready to embark on a high performance program.

PROGRESSIONS VERSUS INSTITUTIONALIZED LTAD & TALENT ID PROGRAMS

When we originally proposed this module we thought long and hard about the title, and settled on “Progressions” rather than “LTAD” for very specific reasons. Namely, that from our experiences traditional LTAD concepts and models (as well as being bastardized) are not backed up by valid measures or works: There is no proven LTAD model over time that we can personally reference as consistently producing healthy, happy, senior level athletes.

Much of the work in this area that has been promoted as the “way” has been lightly tested and implemented by academic theorists. We are not aware of any real time, real world centralized projects that can claim construct, and content, validity and reliability.The football academies in Europe. The AIS model. The German attempts at athletics regionalized centers. U.S. select teams and academies: Few have achieved their promises of becoming the panaceas of talent production. Further, we are not fans of this model in the broad sense as these approaches rarely focus upon the most important aspect of development next to talent: Coaching.

We are confident in our assertion that in the West, institutionalized “LTAD” models rarely if ever work; and arguably not in the East. This is largely because:

a) The right talent never makes it to the centers.

b) The coaching often isn’t what it should be, especially in “academies”.

c) It is too disruptive an environment for youth athletes, especially if they have to relocate.

Instead, what we are advocating is the education of coaches on the principles of athlete development at all stages of growth and maturation. This should be occurring in all locales and environments. This approach allows coaches to arm themselves with the necessary information to develop their own systems of development, and – in the best case scenario, produce athletes that fulfill the criteria for success we discussed above: Or at the very least – do no harm.

It is our assertion that centralized “systems” do other damage: They do not allow for coaches to grow! Too many to count are the number of times we have seen athletes lured away from talented up-and-coming coaches by sport “leadership” because they feel the athlete would be better served in a “center” environment. While this is often a necessary course of action for funding purposes, it is not always desirable. Depending upon the sport in question, it is a 50/50 proposition at best. Often such migration does not allow for the original coach to grow with their talented athlete. It is therefore the responsibility of our sport leadership and federations to find ways to make this happen for the good of sport. This starts with the affirmation of coaching and coach development as a priority.

ALTIS President and Sprint Coach – Kevin Tyler – in his past role of UK Athletics, did world leading work in this area. We asked him to contribute some thoughts to this point:

“Centralized environments are by their nature exclusionary. For every athlete brought into the center there are likely going to be multiples excluded. Unlike sports with small populations, such as rowing and cycling, athletics is not equipment and specialized facility dependent. Over time, coaches and athletes have consistently demonstrated an ability to be successful from a wide variety of environments. Development programs should therefore facilitate this process, not disrupt it.

Centralized environments also tend to be conflictual. With energy and resources primarily focused on the center, coaches and athletes outside of the center are often marginalized. Hence when coach / athlete pairs outside of a center are successful they are less likely to cooperate with National Sport Federation policies and programs.

Instead, we believe in a Coach Development model that is inclusive. When coaches are valued they are more likely to be productive and cooperative. Further, the participation numbers required for a successful national athletics program requires thousands of skilled coaches working from all corners.”

Kevin Tyler

SO, CAN CENTRALIZATION EVER WORK?

In certain cases, for certain sports – yes…

But there is a big ‘if’:

a) Yes – if the center is prioritized around coaching (rather than facilities and support staff).

b) Yes – if the center promotes and nourishes coach development within its feeder system. In this context it is then not the “system” that is the priority, but rather the coaching; coaching must always be the priority for sport systems to evolve.

In addition to all of this, often connected to such ill-advised attempts at institutionalized athlete development are ‘talent identification programs’ (TID). The only thing worse than the institutionalized LTAD systems (or whatever they want to call themselves these days) you see springing up everywhere are institutionalized Talent ID programs. Have you EVER met a successful athlete that came from one? For the amount of dollars we pump into them they have offered appalling results … what a waste. Coaches are, and always have been, our best recruiting tool.

Often, TID programs are nothing more than misguided attempts by sport administrators to formalize what happens organically and naturally within the coaching community every day; everywhere; with everyone. These programs consequently only serve to interfere with the coaching process, and consume valuable resources in communities where resources are scarce. The only “Talent ID” these organizations should be involved with is to identify their best young coaches and start writing them cheques.

Further discussion on the centralization debate

PERFORMANCE STRUCTURES

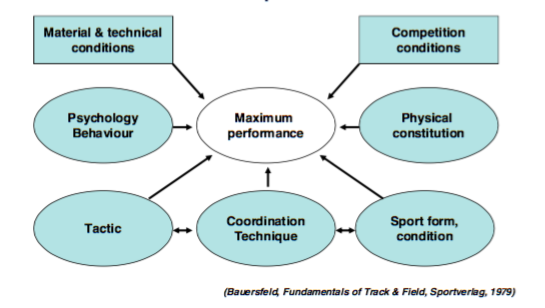

Before we begin the next discussion – we want to clarify a key point on what we are referring to here; when we use the term “Performance Structure” we are speaking of something very specific. Namely, a set of performance indices that have been collected by various researchers / coaches / institutions over time, which list standards for various levels of performance in any given event. But be aware, these standards can vary wildly from country to country; coach to coach; researcher to researcher; and must be taken with a massive grain of salt. They can – when misinterpreted – cause more harm than good. The classic example of this is of the coach who thinks an athlete under their charge is deficient in one area, so sells the farm in order to increase that one test item: often to the detriment of all others, and specific performance. This is exactly why we tell coaches to build on strengths, not weaknesses.

For every event there is a minimum standard for various biomotor abilities that an athlete will typically have before gaining a result. The performance structure provides coaches with an understanding of what they’re working towards when developing long term progressions: It’s very difficult to design a long term plan, if you don’t understand what the demands are going to be when the athlete reaches high performance training.

However, you must be aware that a common mistake made by development coaches is they take what they see high performance (HP) athletes and coaches doing within this context, and employ it directly with young athletes. A lot of developing and teaching has gone into what you see in HP athletes. What coaches should instead be saying is ‘how do I prepare my athletes for this down the road, so they have a physical literacy and skill tool box appropriate for their age and experience?’ That is the hallmark of great developmental coaches – coaches who are willing to sacrifice those short term results, for the long term benefit of the athlete.

Correctly training abilities appropriate to the individual, with appropriate progression patterns is what separates a systematic, structured development system from chaotic or random development. Following a performance structure can help coaches achieve this. When used correctly (and with intelligence) a performance structure is essentially a road map – it is the specific set of specialized physical requirements deemed necessary for success in a particular sport, at the high performance level.

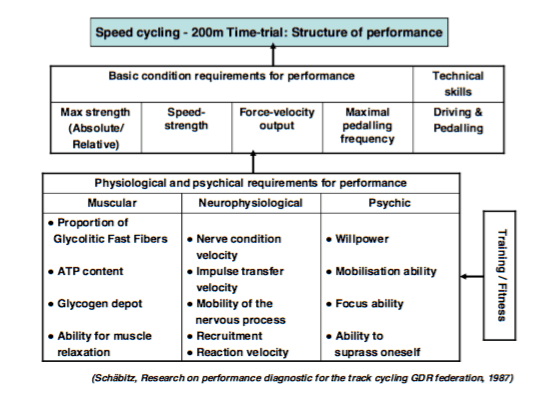

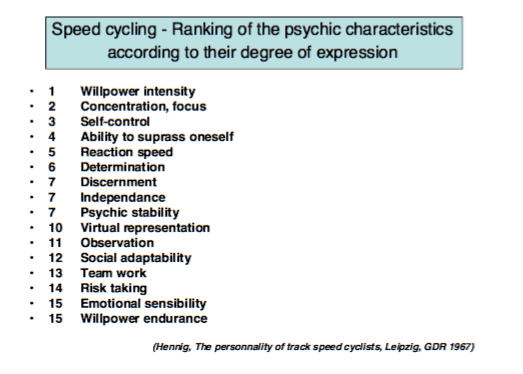

The Germans have historically been very big on this. The following example from the GDR reveals what such a structure looks like. (In this particular example, it is specific to their own elite cycling sprinters; but they also had outliers in their team who were precisely detected with the specific test batteries). Performance structures such as these helped coaches and scientists to design general training plans (labelled RTP in the diagram below) as well as individual training plans (labelled ITP) – which were of paramount importance for these outliers.

Further discussion on the above slides

The reality of being a coach who follows correct progressions – advice and experiences

- Carefully considered training progressions underpin long term planning strategies. Progression is a requisite for improvement over time

- Implementing correct progressions ensures loading over time is appropriate, loading is balanced across key abilities and movements, and the introduction of specific loads occurs at the appropriate age

- Progression patterns explain the progress over time of a given individual or group of individuals, in various specific biomotor or psychological qualities. What these patterns look like will very much depend on the population and specific sport being observed

- Implementation of short-term progressions is critical for short to medium-term peaking, and form attainment across an annual plan

- Long term progressions rely on the step-by-step introduction and development of key abilities over time in order to create a stable base for the future

- We are not centralization fans in the broad sense as these approaches rarely focus upon the most important aspect of development next to talent: Coaching

- “Performance Structure” defines a set of performance indices that have been collected by various researchers / coaches / institutions over time, listing standards for various levels of performance in any given event

LTAD

Talent ID

Progressions

Performance structures

Reading: The retention of elite players after a junior career (squash).

Reading: Career transition from junior to senior in basketball players.

Video: This extended learning video, hosted by Nelio Moura* shares the Brazilian approach to LTAD and the road to High Performance.

*Nelio Moura is one of the world’s leading jumps coaches. His position as such was cemented into place at the 2008 Beijing Olympics when he coached both long jump event winners – Maurren Higa Maggi of Brazil, and Panama’s Irving Saladino.